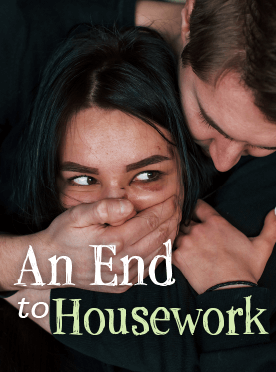

An End to Housework

Synopsis

Newly divorced 32-year-old Violet crashes her motorcycle into a pickup truck and ends up the captive of cunning and reclusive survivalist Alex Finn. She must convince Finn’s nephew Bay to help her escape, or she'll never see her young son again.

An End to Housework Free Chapters

CHAPTER I: BEFORE THE ACCIDENT | An End to Housework

↓

“I don't want to play hide and seek anymore,” said Jessie.

Violet looked up, startled. Her son could be so quiet. She had been intent on not thinking about Calder packing things in the house that she hadn't heard Jessie creep up through the bushes behind the garage.

“You're too good for me, anyway,” she said, standing up and brushing off the seat or her pants. “What do you want to do?”

“Push me on the swing,” said Jessie. He put his hand in hers. “Okay?”

“Sure, Jess.” They walked together across the yard to the swing, which hung from a tree near the back door of the small white house—more of a cottage, really, or so she'd always thought.

“The swings in the park where Daddy lives aren't as nice as this,” said Jessie.

Violet let go of his hand. “I'll give you a real good push, then,” she said. Her son gravely sat himself on the swing, looking over his shoulder at her. She smiled and ruffled his hair, thinking How come this kid never smiles? Bending to grasp the edge of the seat, Violet could smell Jessie. He had that little kid odor, not unpleasant, but proof that he hadn't bathed recently. “When's the last time you got in the tub, Jess?” she asked, pulling back on the seat then pushing forward.

“I dunno…couple days ago. Harder, Mommy! Last week, I guess.”

She made a mental note to speak to Calder, not caring if he became annoyed with her opinion of how he was looking after their son.

Jessie’s baggy chinos emphasized his thinness as he swung his legs, adding impetus to his motion. Up and down, back and forth…she lost herself in their shared motion. Everything about this little scene is almost normal, she thought. Almost…except that this was the last time they would ever play together in this yard. The house, a few yards away, looked normal, too, aside from the BANK FORECLOSURE sign, of course. Its inside was empty of belongings except for a last few boxes. Everything else had been sold, moved out into Calder's new Boston apartment, or put in storage.

Calder came stalking around the corner of the house, looking, as always these days, preoccupied and worried. His hair, untidily long when they’d met, was now cut and styled. Seeing Violet and Jessie, he halted and nodded toward the house.

“Can you swing by yourself for a couple minutes, Jess?” asked Violet. “I have to talk to Daddy.”

“Okay.”

Violet walked slowly across the lawn, thinking that Calder looked as if he had aged two or three years in the past one. Gray had sprouted in his hair; one reason he’d cut it, she was sure. His ulcer was bothering him again—his face bore the telltale pinched look and there was a vertical line between his eyes.

“The truck’s all loaded up,” he said.

“Thanks for coming down to supervise.”

“No problem. I knew that I could get it done faster than you,” he said in a typical display of unconscious condescension. “I'm surprised you didn't want me to call the rental place. I know how you are about talking to people on the phone.”

Her face grew warm. “Are you trying to pick a fight, or—?”

“No, no,” he said, holding up his hands, palms toward her. “Uh, how's the bike running?”

Violet glanced at the Kawasaki Vulcan 88SE parked at the head of the dirt driveway. “Fine,” she said, still annoyed at him. “I appreciate you lending it to me for the trip.”

“Yeah…well, there's no place to park it near my new place where it wouldn't get stolen or vandalized, so it's okay for you to hang on to it as long as you like.”

“Uh-huh.” Glancing at the foreclosure sign, she repressed a surge of anger. This wasn’t the time or place for a confrontation. They’d had enough of those, anyway. He’d been without a job through much of their marriage, but she’d trusted him to look after their finances because of his background as an accountant. By the time his ineptitude and gambling habits came to light, most of their savings were gone.

“I’m going to miss this house.” He paused. “Listen, you know—I’m sorry.”

She shrugged. “Sure.” He’d gotten the help he needed, through therapy. His demons were under control, he had a new job and a new lover, and the disruption of divorce was behind them now. The silence grew awkward.

Finally, he smiled. “What are you going to get me for my birthday?”

“Your birthday?” She snorted. “A box full of tears.” At the angry look on his face, she said quickly, “I'm sorry, that wasn't fair.”

“Yeah.” He paused again and turned to go, then added, “Vi, do you think we’ll ever be friends? I'd like to be your friend.”

“I don't know. Ask me again in five years.”

He nodded slowly. “Yeah. Right.”

She walked back to the swings. I've got to get out of here, she thought. She didn't even want to be around her son.

“How long you donna be gone, Mommy?” asked Jessie as she started to push him. At four and a half, he was still getting his g’s and d’s sorted out. Tests for dyslexia were inconclusive but it was, as the doctors said, something to watch out for.

“A week or so Jess,” she replied, pushing him again on his way down. “I'll see you soon's I get back…I'll come up for a weekend.” Her leather jacket creaked and sighed. “Promise. And we’ll be together for Thanksgiving.”

“I wish I could go,” he said the next time he came level with her head.

“You'd have a tough time, walking down trails with forty pounds of pack on your back. That's how much I'll be carrying.”

“I'm not so little. I'm nearly five!”

“No, not so little.” But he was. In a way, it was good…he was a very adaptable child. His parents’ split had been hard for him, but he was adjusting well. He liked Boston and got along well with his father. He liked Calder’s girlfriend Maureen, too. Violet supposed that was for the best. Until she found herself a better job than waitressing, there was no way she could afford to keep Jessie. Two months alone in the small house had convinced her that it would be prudent to move back in with her folks for a while, even if it meant returning to Connecticut. The house had been too depressing an environment at any rate.

Calder, carrying a box, came walking around the corner of the house again. He had acquired a smudge of dust down the side of his nose in the past few minutes. Maureen, Violet knew, a compact, dark little woman who worked with horses, was a real Type-A and would have made him stop while she wiped it off with a tissue. Maureen’s presence made Violet uncomfortable. She was glad that Calder hadn't brought her along.

“Everything's all set, Vi,” he said, putting the box down. He stood with arms folded as he watched her push Jessie on the swing. “We can leave any time you're ready, Jester,” he added to his son.

“In a minute, Daddy, please? I wanna swing some more.”

“Okay, but only for a minute. Huh—” He’d been about to say hon, Violet knew, and she all but flinched. “Vi, I’m going to lock up the house now. You need to use the bathroom before I do?”

She shook her head. He turned and stalked away. “Your dad looks like he's losing some weight,” she said to Jessie. “Is he getting along with Maureen?”

“Yeah…they don't argue so much anymore.”

“Well, that's good, anyway.” She remembered Jessie telling her, almost tearfully, about the shouting matches Calder and Maureen had had during the early weeks of their live-in relationship. At the time she had wondered if she had been wise in granting custody to Calder. Not that she’d had much choice; though his lies, evasions and (she’d learned) infidelities led to their divorce, he’d hired a vulpine lawyer who because of her past painted her as drug-addled and a religious cultist. Calder, with his new haircut and his new high-paying job, was awarded custody of Jessie. The lonely nights spent worrying about Jessie had been very bad for Violet; had, in fact, convinced her to leave Rhode Island. Back with the “rents” at the ripe old age of thirty-two…

She sighed. “Does Daddy take you to the park much?”

“I guess so,” said Jessie.

“Do you have some friends there?”

“Couple. Mommy, will you come to live in Boston?”

“I don't know, Jess. I don't think so. Your Gram and Gramp have my old room for me in Danbury till I get a job…that's the best bet, for now. Then you can come stay with me.”

As if her answer had robbed him of energy, Jessie stopped pumping his legs. The length of his arcs lessened. “I wish you and Daddy didn't have to be duh-vorced.”

There was nothing she could find to say. He was still too young to understand how love worked—or didn't work. Love was love, to five-year-old: it was there, it didn't fade, it didn't turn bitter or painful. “Come on,” she said after a moment. “We better be on our way. Your dad wants to get back.”

“'Kay.” He slid off the swing, leaving it rattling and shaking on its chains. He walked a few paces then broke into a run. Violet followed more slowly, listening to the chains jangle coldly behind her.

Red-faced, Calder slid the tailgate ramp of the rented truck into its slot, banging it into place. Sweat dripped in his eyes. Violet knew better than to offer her assistance. Ignoring him, she went over to the motorcycle and inspected the saddlebags and her backpack, which was strapped to the sissy bar on back. Everything was perfectly secure.

Given copasetic traffic patterns, she would be in Bridgeport in about three hours.

“All set?” called Calder from the rear of the truck. She turned, seeing him wipe the perspiration from his forehead.

“Yeah,” she responded.

“Us, too.” In his Ned Flanders voice, he added, “You about ready, Jesteroonie?”

“Uh-huh.”

“Okely dokely then, up you go.” Jessie obediently climbed into the front of the cab. Violet went over to him and put her arms around him through the window.

“I love you, Mommy,” Jessie said softly.

Oh, don’t you dare cry! she admonished herself. “I love you, too,” she whispered, kissing him, then let him go before she began to weep. “You behave yourself and listen to your dad.”

“I will.”

Calder was standing next to her. He put a hand on her arm, squeezed, and said, “You be careful driving that thing on the highway. I don't want to have to come picking you up from some rural emergency room.”

His tone was light enough, but the words stung her anyway. “You won't get any calls from me,” she said. “Thanks for the help. I’ll see you.” She turned around and walked to the motorcycle.

She zipped up her leather jacket and took the helmet from atop the gas tank. It buckled under her chin. Calder started the truck as she swung a leg up and over the tank to mount the bike.

Key in the ignition. Twist it on. Engine fires right up. Right hand: throttle. The motorcycle idling beneath her felt good. Right foot, now on the rear brake pedal. Soon a step forward, for balance, thrusting the bike ahead as the left foot tapped down into a higher gear. Foot-tap, kickoff, as simple as that, before she was quite ready. “Bye-bye!” she called to Jessie, surprised, as she bumped past the truck creeping down the driveway. In the rearview mirror she saw Jessie's hand wave out through the window.

Down the short drive, dusty orange dirt rattling with crisp fallen leaves of yellow and deep red. At the base of the incline the driveway opened diagonally into the intersection of Routes 116 and 7. South along 7 a dozen or so miles was Providence. There she would pick up the I-95 heading south.

There was no traffic on the two-lane road in the afternoon. People were at work on this Friday, or cleaning house, cooking supper for their kids and husbands.

Behind her were her kid and her husband. Well, no, she reminded herself—ex-husband. Behind her on the bike, strapped and wrapped, were also the things of her life that she had chosen to take with her. Inside her, the things she didn't want to take along accompanied her as well.

I would like to lose them on the road as easily as I'll leave Calder and Jess behind in the truck. I need the road. Such a strange thought…homebody me, I never needed it before. It was always just a way to get to a place. Now it's a place of its own.

Just south of the intersection stretched a region of old farmhouses and desolate fields, the northernmost last gasp of the city's grasp for land. She twisted speed into the Kawasaki, accelerating into the farmland. The sun burned through the edge of a cloud and sent a beam off the gas cap in front of her into her eyes.

This was like a slap: she would never see the small white house with the charming red trim again. The sunbeam photographed the image of the house in her mental camera. She had been happiest in that house; she had been saddest in that house. Never would she have believed that she could be so relieved to leave it.

Topping a ridge, she saw a glitter of sun off water near the horizon: the Providence River, separating East Providence from Providence itself; a city sandwich of water.

The influence of the urban region ahead increased almost as soon as the city came into view. Traffic grew heavier. The shabby homes along the road morphed into more expensive ones, many with small signs proclaiming the residents’ preference for one presidential candidate or the other. Other signs read FOR SALE. There had been more of these of late. A mile or so after she sighted the city the road threaded between two ponds near a golf course. Just beyond was the restaurant where she and Calder had celebrated their sixth month of marriage. She sped past without looking at it. Then came a section of condominiums (clowndomniums, Calder always called them) crouching at the outskirts of the city's sprawl. Past the condos a hill dropped the road into a junction with Route 15, along which she and Calder would usually go to shop for groceries at the Almac's and grab a bite at the Pizza Hut, which Jessie loved and both parents execrated as Lovecraftily demon-haunted, appropriate for Providence but certainly not for dining.

Got to stop thinking about all that old stuff, she said to herself, looking up the road at the stores and traffic. Think about Bridgeport, Deb and Paul, it’ll be good to see them, spend the night before heading up to Danbury tomorrow morning.

Deb and Paul had been at the wedding. They were part of the past, too—Violet was not sure that she could relax with them now. They had not changed; she had.

Two years ago, she would never have so much as dreamed of riding a motorcycle, let alone taking a five- or six-hundred-mile trip on one. Calder bought the bike for recreation (back before she learned to question his spending habits) and forced her to learn how to drive it. She discovered that it was really a lot of fun, and easier to care for than a car. Being good with her hands, it didn't take her long to get interested in maintaining the vehicle in good running condition. She didn't let Calder's faintly condescending attitude toward her interest bother her.

The light at the foot of the hill turned red and she slowed to a stop. She stood there, straddling the bike, looking around. It was good to feel isolated behind the faceplate of the crash helmet. The light changed.

It was easier than she had hoped to keep her mind on her driving. The memories weren't going away, but they were easier to ignore while she was concentrating on something else. She turned on the Kawasaki’s radio and let NPR distract her further with segments on Obama and McCain.

Around her the city was now in full blast. Liquor stores, corner delis and mom-and-pop groceries, florist shops, kids on skateboards on the sidewalks—it all condensed into the North End. Music pounded out of passing cars. As she drove further in toward the center of the city the homes became nicer, but the people drained away and the neighborhoods seemed peculiarly empty. No one moved on the streets; the cars were too clean. Then, as if the city blinked and shook itself, Violet found herself driving between gray warehouses among glass-littered parking lots. Dilapidated apartment houses leaned against one another, crowding hungrily around a McDonalds. A sign reminded her of the interstate entrance, three blocks away.

She saw an old black man pause shakily on a street corner to light a cigarette.

Remembering that she needed to buy some smokes for herself, she pulled over in front of a small bodega. No one was in sight; she decided she could leave the bike unattended for a few moments.

She dismounted and stretched, feeling her muscles complain briefly as she knit her fingers and flexed them. Then she bent her arms abruptly to crack her elbows.

The store’s facade was of corrugated green metal, as sad as an abandoned Army barracks. Unbuckling her chinstrap, she entered.

Dim daylight filtered in through the dusty front window. Round metal racks filled much of the available floor space between crowded shelves and glass-front freezer cases. The floor was dark stained wood, almost oily in appearance. To Violet's immediate left as she entered sat a high glass counter filled with cigars and candies and hair beads and batteries and thread.

Behind the counter reading a worn paperback sat a woman, fiftyish, plump, with very dark skin and a wide corners-down mouth. She peered through horn-rimmed spectacles at the stocky young white woman standing before her.

“Good morning,” said Violet quietly. “Do you sell cigarettes?”

The woman blinked. She said, “We got some, machine down tha’ third aisle. It's outta some things. Don't smoke myself, so's I don't know what-all's missin'.”

“Thanks.” Violet walked down the indicated aisle. Her favored brand, Marlboro, was among the missing ones. She fed coins to the machine and chose Old Golds. Back outside she lit up standing next to the motorcycle and looked around at the threadbare buildings all around. Providence had nothing more for her. She felt the city was pushing her out of itself like a splinter from damaged flesh.

She ground the half-finished smoke out under a boot heel and got back on the bike. Up the ramp, then, and onto the highway through city center. She guided the bike to the far-right lane, keeping alert in the stream of mid-day traffic.

She gave a glance to a favorite landmark as she passed the large building that housed New England Pest Control. Atop their headquarters, the company had erected Nibbles the Big Blue Bug, an enormous locust-like insect larger than a semi-truck. Nibbles was dressed appropriately for holidays: a stars-and-stripes top hat (and white goatee) for July 4th, witch’s hat and mask for Halloween, and so on. Even in her low mood this silly statue made Violet smile a little. Then it was behind her. The buildings thinned out. She was truly away, now, out of the city forever.

Ahead, the multiple lanes were rapid with cars and trucks of all descriptions. Her ears filled with the endless rush of wind around her helmet. The sound pressed her jacket back, rattled and batted at the windshield. Along the horizon, below the westering sun, lay a long line of comma-shaped clouds, looking like the results of a stuck key in some celestial computer, but for the most part the sky was clear.

Lane lines flashed by beneath her feet, paled by the slanting light.

Countryside replaced city along the highway. After a while she began feeling hungry. About twenty miles south of Providence she exited the highway along a circular ramp. Not far away was a small strip mall she had visited once or twice in the past.

Then she remembered that the only restaurants there were a pizza place and a Chinese take-out. She wasn't in the mood for either. She realized that she wasn't in the mood for a strip mall, either, but her stomach required food, so she kept on.

A quarter mile or so before the shopping center, parked next to a boarded-up gas station a small red-and-white striped trailer bore a hand-lettered sign reading HOT DOGS. Violet pulled in.

She dismounted from the bike, took off her helmet and rummaged for a cigarette, enjoying the quiet after the steady rush of wind on the turnpike. Through the screened window along the counter in front of the food wagon she saw yellow plastic squeeze bottles with red printing on them. The odor of grease and frankfurters stained the air. Walking to the wagon she lit her cigarette with a plastic lighter.

The window slid back with a loud rasp. A young woman of about 16 looked up at her, arms folded on the counter, peering along a blunt nose.

“Hi, what have you got?” asked Violet, looking for a printed menu on the walls. She saw nothing but old fly-specked wooden shelves sparsely stocked with bags of buns, large cans of mustard, and boxes of coffee for an automatic coffee maker.

“Hot dogs,” said the attendant softly, eyeing Violet's leather jacket. Her eyes flicked to the motorcycle and the bulging saddlebags, then back to Violet.

“Just…hot dogs?”

The young woman nodded. Her long thick hair seemed to be dragging her facial muscles down. Her eyes were red. Hungover? “Yeah. Hot dogs, with relish or bacon or mustard. We're out of bacon. Can’t get more till the fridge is fixed.”

“Well, how about a couple of hot dogs.”

“Yes, ma’am. Coffee?”

“If you haven't got any soda…”

“No. Just coffee…and hot dogs.”

Violet sighed. “No 7-Up or ginger ale? Okay, coffee. The caffeine will do me some good. Got any milk or cream?”

The young woman threw a disgusted look around at the inside of the wagon. “Not with the fridge out, I guess. Artificial creamer.”

“That'll do.”

“Or condensed milk,” she finished, holding up a maroon and white can.

Violet had never seen the thick glistening liquid before. “I'll try some of that, please.”

The girl busied herself with the grill. Violet noticed a curl of flypaper hanging in one corner of the wagon. Turning her back to the window, she leaned against the counter and studied the road.

It would have been a good time to have a profound insight about her failed marriage or the reality of having to remake herself at the age of thirty-two—but nothing would come. Instead, she blankly watched cars slide past and smoked her cigarette, without so much as one intelligent syllable forming in her mind.

Presently the screen slid back. The attendant placed a Styrofoam cup of steaming coffee on the linoleum counter. Violet picked it up and sipped. The coffee was very hot. The condensed milk added a thick pleasant sweetness that surprised her. She liked it.

We'll have to get some of this. Calder might like it—

Then she remembered. Calder was living in Boston with his new love, Maureen.

The hot dogs were hardly worth waiting for. Blistered black along one side, they lay curled painfully in their soggy rolls. She munched them unenthusiastically, losing more appetite with every bite.

Her attention wandered across the street to a café set back about twenty feet from the road. The food probably would have been better over there but there was no point now in such speculation. The building had the façade of a log cabin, painted dark green. Three TV antennae sprouted from its high peaked roof. Several cars sat in the lot including a state police cruiser parked next to a blue pickup with a (empty) gun rack in the rear of the cab.

A high buzzing roar grew from her left in the direction of the highway. She turned to mark it, swallowing the last of the hot dog. Under the turnpike bridge came a motorcycle ridden by a helmetless man. He seemed to be heading for the café, but apparently caught sight of Violet’s bike because at the last minute he jazzed his machine a little and swept into the abandoned gas station's lot in front of the snack trailer. He parked his bike, an old red and silver Indian road eater, next to hers. Her Kawasaki suddenly looked like a glittering toy.

He was not tall, not fat, not young, with the graying, receding hairline of a man in his fifties. His face was seamed, mobile, smiling, and dark red. He shut off his machine and swung his leg easily over the tank.

“That yours?” he asked her, angling a thumb at her shiny, undented bike. His voice was a long dry creak. It sounded familiar somehow.

She nodded, feeling nothing other than some impatience. There was no time for come-ons.

“If you're passing through,” he said, turning to look at the cafe across the road, “and I guess you are because I never seen you around, you should take it slow between here and the Connecticut border.”

“Speed traps,” she said and sighed. “I know.” Then she placed the voice: he sounded like the actor George C. Scott.

“Oh, so you do? Okay.” He grinned broadly. “Sorry to have disturbed you.”

“You didn't,” she said—a little too tartly, she realized. To cover her discomfort, she swirled her coffee in its cup and drank.

“That fellow over there,” he said, nodding at the state police cruiser across the street, “is on his lunch break, but there are three others between here and the truck stop at the state line. Hi, Janie!” he added to the young attendant. “How about a coffee?”

“Okay,” said the teenager, without smiling.

“My sister-in-law,” he said to Violet in a confidential tone. Violet glanced at him, beginning to relax. This was no come-on. His eyes were very blue in his dark face. “She thinks I'm a little crazy, you know, because I’m the only one in the family with a motorcycle.” He laughed.

Violet finished her coffee and threw the cup away but made no move to get back on her bike, feeling that she owed the guy some civility. “Thanks for the tip about the speed traps,” she said. “Sorry I snapped at you.”

“No problem! You know,” he said, grimacing, “I like to beat these cops out of their quota if I can. Last day of the month, you know what I mean? The last-minute push, for billing purposes…pain in the ass, they are.” He paused to lift his coffee from the counter without replacing it with any money. “Most places, along the big highways like this, they got the radar out where you can see it if you know where to look. Not that most folks do.”

“Yeah?”

“Sure! Come on, you seen 'em…the radar guns are supposed to be where you can see 'em, law says so. Even in their cars. But around here, they stick 'em behind bridges, in bushes…sneaky.” He sipped at the coffee. “Aaaa. Never enough sugar, that girl. Anyway. First time I hit this trap, coming up here to spend some time with my brother and his family, I went sailing past this cop. He was behind a bridge, waiting. Sneaky. Ah, ha, I said. I pulled off the next exit, went up the ramp and came back around.

“So there I was, in front of the speed trap again and I slowed down to forty miles per. Traffic backed up behind me, oh, about ten cars. So the cop sees me, races out, and pulls me over. He gets out of his car and swaggers up to me…they can’t help that swagger, it’s from all that goddam hardware they wear round their waist and hips…I say, what’s your problem, officer?”

His raspy voice gave the rendering of the question a razor edge of sarcasm. Violet smiled.

“‘What's my problem,’ he says. ‘What's your problem, fella?’ ‘Oh,’ I says, ‘I don't have a problem. You pulled me over, what's on your mind?’

“Well,” he said pausing after a sip of coffee to look in Violet s eyes, “he said I was goin’ too slow.”

Violet smiled again.

“Too slow! And he wanted to give me a ticket for it. Ha! I says. I got dozens of tickets, all for goin’ too fast. No way will judge believe me goin’ too slow.” He paused to drink again. “I knew what he was after…he wasn't going to catch any speeders with me blocking the lane like that.”

“So did you get the ticket?”

“A written warning,” the man said, and laughed. “For goin’ slow, sure enough. They'd never believe it. Too slow.

“Well look, I gotta head out. Take care and watch out for the traps.”

“Thanks, I will,” Violet said, shaking his big, rough hand. “Nice talking with you.”

“Likewise, likewise,” he said, matching her slight pressure. “No one to talk to around this little town except my brother, and he’s usually at work.” He sat down on his machine as she started hers up.

Back on the turnpike, in the late afternoon, reddening light filled the rush of chill air, sliding off cars and giving the roadway’s concrete and asphalt an illusion of warmth. The colors of the day were so beautiful that she got lost in them for a while. The clouds above were edged in intense gold, shading to the hue of French vanilla ice cream.

Not long after crossing the border into Connecticut she saw the exit sign for Westbrook, where she and Calder had vacationed a few times, in small, rented beach houses.

Jessie had been little more than a toddler. She remembered one perfect twilight in particular, a warm evening in late June. A vivid image: Calder ambling down the cement walk onto the sand verging Long Island Sound, holding Jessie's hand in one of his and Jessie's pail in the other, while Violet watched from the porch.

She shook the image loose and concentrated on the road, allowing herself to feel the cold wind. Sighing heavily, she blew breath out between stiff lips.

Arriving in Bridgeport an hour later, she exited I-95 onto a feeder road that took her down into the city along North Avenue.

She was growing tired. The buildings and businesses crowding the road were like those in Providence. She had an odd impression of having traveled nowhere despite the miles ticked off on the odometer. The same fast-food places, carpet stores, liquor stores, cell phone stores…A few people pointed and stared at the unusual sight of a woman on a motorcycle, and a scrawny Hispanic kid called out something in Spanish.

Heading north she entered residential neighborhoods. Here the nucleic confusion of Bridgeport's center was not evident as the city shaded off into suburbia. Several blocks up East Main she approached a busy intersection bracketed by two large gas stations crowded with cars. Just prior to entering the intersection she turned right into Louisiana Avenue, a street lined with multiple-family semi-detached dwellings. The first building on the left, however, was the oldest one on the street and the only single-family wood home. Its number was 5. She pulled into the driveway.

The house was small, peeling, shingled with gray asphalt tiles. She got off the bike and stretched, noticing that the lawn hadn't been mowed recently. Knowing Paul, come the first week of October he’d put the lawnmower in the garage and said, “That’s it until April.”

She clumped up the sagging wood steps and twisted the bell handle in the center of the front door. It rang sharply. Waiting, she peered into the window on her left. The living room was empty. Violet folded her arms.

She thought that her reflection in the glass of the door looked pale. Helmet-head, she thought, squinting critically at herself, and fussed at her hair to restore some sort of life to the heavy curls that had been flattened inside her crash helmet.

The motorcycle ticked and pinged behind her as it cooled. She remembered Calder jogging alongside her as she took her first solo ride, calling encouragement to her.

The bike wasn’t really meant for long distances. Calder had bought it to use on short hops into and out of Providence. As a newspaper reporter, he spent a lot of time running around the narrow up-and-down streets of the hilly city.

A minute and a half at the door…no answer. She checked her watch: after six. Deb and Paul should have been out of work. They'd probably gone food shopping and were stuck in Friday traffic.

She lit a cigarette and sat down on the steps to smoke it. By the time she was done, she was feeling restless, so she got up and walked around to the back of the house.

The back yard wasn't mown, either, and the small flower garden that an earlier tenant had planted had been since allowed freedom from cultivation. A thick net of rosebushes had all but digested the garage, a sagging structure, like a floral Blob engulfing a diner. The wildness of the back yard, underscored by the white noise of nearby traffic, made her feel lonely. It was her nerves, she decided, walking aimlessly through the grass. The long ride down from Rhode Island had jangled them.

Taking a deep final drag on her cigarette she walked over to the garage and peered in through a grimy window. There was nothing inside on the dirt floor save for some sticks and a few bits of miscellaneous flotsam. She tried lifting the door, found it unlocked, and raised it all the way. Dust and pieces of trash fell on her hair as the door groaned upward. She went back for her bike and rolled it slowly into the garage. No point in leaving it out in the open for people to see, not with all her camping gear and clothing strapped to it.

Closing the garage door, she walked to the front of the house and turned right, heading for the intersection. Although she was tired, anything was better than sitting around by herself, and a little walk, she felt, would do her good. Going for a quick visit to the zoo where Paul worked would at least give her something to look at besides overgrown lawns. When the light changed, she jogged across the road despite the weight of her boots and leather jacket, anxious to get as far away as possible from the fumes and noise of the cars. Without pausing or slowing she chugged on up the park’s asphalt drive past a large wooden sign. Gold letters against an unpainted background read BEARDSLEY ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS. At the top of the small rise, she slowed to a walk, not wanting to appear conspicuous.

Though it was nearly closing time a few people were still there, mostly couples with children.

She walked into the main area of the zoo. Seals rollicked in an enclosure to her right, splashing in the honey-colored sunset. Jessie loved seals and penguins…A young mother strolled by, holding the hand of a boy about Jessie's age. With every step he took, LEDs in the soles of his sneakers flashed. Violet frowned and turned away. Maybe coming to the zoo hadn't been such a good idea after all.

In front of her was a brick building that housed monkeys and some other animals. On impulse she decided to take a quick look.

Inside, the one-story brick building was warm and echoing. Raucous squawks reminded Violet of Paul’s mention, in a recent e-mail, that several new exhibits had been added. These included some tropical birds, one of which was now shrieking, as well as some tarsiers, a pair of gibbons, and Paul's favorites: two young leopards. In his more than five years at the zoo, she couldn’t remember Paul ever sounding more excited. Violet had not visited Bridgeport since before the arrival of the big cats.

She remembered the building as smelling differently. The new animals here would certainly add their own scents to the mixture, she knew. The odor was odd but not unpleasant. In the center of the building, where there had been no enclosure in years past, a new one had been built, lit by a bank of spotlights. Violet approached slowly, her hands deeply thrust into the pockets of her jeans.

A large cage, perhaps twenty by fifty feet, took up most of the available space. Surrounded by a high barrier of plastic, it held two leopards. One, the female, lay on a rock warmed by the floodlights. The other, a bobtailed male, paced restlessly, ignoring the thirty or so people clustered in small groups around the cage. Almost no one paid any attention to the other exhibits in the building; the monkeys sat in boredom, and the birds, except for the agitated toucan, emitted listless cries. Clearly, the beautiful big cats were the draw.

Magnificent creatures, Violet thought, particularly the male. She moved up to the handrail, staring. His rich coat shone brilliant white, glossy black, hot yellow orange. Beneath it his muscles rippled with easy power. The emeralds of his eyes glittered from a head like a block of ivory. He paced ceaselessly, panting, lower jaw ajar revealing teeth and fangs.

A few feet to Violet's left a small child asked her mother, “How come they puts plastic ‘roun’ the big kitties?”

“Dat I don’ know,” was the reply. “I guess so’s people won’t feed ‘em things that ain't good for ‘em.”

A few moments later the leopard stopped pacing. It swung around so that its hindquarters faced the Plexiglas shield. With surprising accuracy and force, the animal squirted a bullet of urine at the onlookers. The stream splashed against the plastic.

The person directly in line of this attack, a small olive-skinned man with large mustaches and calloused hands, recoiled, blinking. Then he laughed, sheepishly. Others joined in, but several people looked curiously at him.

Violet raised her eyebrows and, nodding, leaned on the railing, viewing the cat with new respect, thinking, I know how you feel. Must be frustrating, stuck in there all day, smelling monkeys and birds and being hungry for something other than a pan of stuff or a cold haunch or whatever, and not being able to get out for a hot meal. She was a little surprised at herself; not so long ago she would have felt sorrier for the monkeys cooped up in their small cages, not allowed to swing through jungle trees.

The leopard seemed more pitiable now than the monkeys. She was glad that she had been in to see the animal, but ultimately, she felt, he would be better off uncaged.

The huge feline resumed pacing.

She left the building and walked back down the drive toward the intersection. Across the way, she saw her friends’ Honda Civic parked in number 5’s driveway.

As she approached the house’s front porch she heard, faintly from inside, a tune that she recognized as “Pop Party” by the Poodle Boys. Paul was a devoted fan of punk and indie rock, and had played the record for her on her previous visit. She twisted the bell on the door. Within a few seconds, Paul was in the doorway.

“Hey, Violet, I didn't hear you drive up.” He was only a couple of inches taller than she, slight of build, with coarse, gray-shot hair and a beard to match. His eyes, lively blue, moved as quickly as his long-fingered hands. He threw his arms around her for a hug and gave her a quick kiss on her mouth. Standing aside for her to enter, he kicked the door shut behind her.

“I parked my bike in your garage,” she explained, shucking her jacket and tossing it over the dilapidated chair that was the only piece of furniture in the small foyer between living room and kitchen. “All my stuff's on it. You weren't home so I went over to zoo for a while.”

“Hi!” called Deb from the kitchen. She appeared momentarily in the doorway, holding a large green pepper. “How was the trip down?”

Violet followed her into the kitchen as Paul turned down the Poodle Boys in the living room. Deb, as small and slender as her husband, was aproned behind a large cutting board, expertly chopping vegetables with a large shiny knife.

“Looks like Chinese to me,” remarked Violet, lowering herself into a chair by the table. As always, proximity to Deb made Violet feel ungainly. “The trip…it was…okay. I’m kind of tired. And hungry.” Deb, smiling, put down the knife and went to give her a hug. Violet was surprised by an impulse to cry against her friend's breasts. The women released one another. Deb went back to the cutting board.

“Chinese it is,” she said lightly. “Vi, you look like you could use a drink. Hey, P.K.?” she called into the living room.

“Yo?”

“Why not take Violet over to the Penthouse for a drink? I've got to get this cutting and spicing done and it'll take me twenty minutes anyway before I can start cooking. Besides, if you play that fucking album one more time I am going to spin around and spit nickels.” To Violet she added, “The band is having another reunion gig in New Haven on Saturday. He’s played fucking ‘Pot Party’ a million time this past week. I told him to put it on his iPod and stick it in his fucking ear.”

“‘Pop Party,’” he said, entering the room holding an album cover. “Not ‘Pot Party.’ It’s meant to be heard on speakers, not earbuds. Christ. But yeah, they’re gonna be at Toad’s on Saturday. Up for a show, Vile? Deb refuses to go.”

“I don’t think I could handle a whole concert of that,” Violet said with a grin at his old nickname for her. “Besides, I’m only staying the night.”

“P.K, go buy the woman a drink,” said Deb. “We have sake and beer for tonight, but I bet she could do some damage to a vodka Collins.”

“God,” said Violet, “that sounds good. I haven't had a decent one in ages.” And it was true; she hadn’t had any alcohol aside from an occasional glass of Merlot in nearly six months. Her lawyer had warned her against drinking during the divorce proceedings, given her past. But it was the drug use they’d really nailed her on.

“In that case, let 's get on over to the Penthouse before the place fills up too much for Happy Hour,” Paul said.

“Just let me change out of these boots…help me get my stuff off the bike?”

“Sure,” he said, placing the album cover down on the table. They went out the back door, across the shaggy lawn to the garage.

#

The Penthouse Bar comprised the second story of a two-floor edifice butted up against one of the gas stations at the intersection. With its attendant parking lot, the building's first floor functioned during the day as a low-rent Italian restaurant named Festa, which Deb and Paul referred to as the Fester. During the noon hours, the Fester provided food for the Penthouse bar, which was open to serve lunch to patrons who might prefer something stronger than orange soda with their cheeseburger or Reuben.

Violet followed Paul into the Fester’s foyer and up the stairs to the Penthouse. The tavern was dimly lit, yet there seemed to be a lot of twilight inside due to a huge mirror running the length of the bar, and from the waxed wooden booths and the glossy surface of the bar itself. All of these gave back colors from the neon beer signs hung here and there on the walls. The arrangement of the three tiers of bottles in front of the mirror—or behind it, depending on one’s point of view—was punctuated at three regular intervals by thick-walled five-gallon jugs containing high-humidity plants. Most of the ambient light, however, was an almost garish mixture of colors from the old ill-tuned TV above the cash register and from a brace of video games against the far wall that occasionally booped and beeped to themselves like senile robots.

Several middle-aged men sat at the bar, leaning on it or against each other to share mumbled comments. There was one other woman in the place besides Violet, a heavy-set black woman sitting with friends at the far end of the bar near the restrooms.

“She's a regular,” Paul remarked as they took a seat away from the others.

“Huh?”

“I saw you looking at her. That's Judy. That guy, the one she just put her hand on his shoulder? He’s her boyfriend, Gerry.”

Judy, who looked to be in her late twenties, was as boisterous as a lottery winner. She laughed often while exchanging jokes with the men at the bar. Her oval face was plain but strong, dominated by glasses. She wore a plain gray skirt and a long-sleeved sweater emphasizing her large breasts.

There was an ESPN yack-fest about the upcoming World Series on the TV and Judy's attention was mostly on this as she joked with the white, unathletic-looking men.

“It’s Friday night again,” Paul observed, and shrugged. “Attitude adjustment time.”

The bartender, a small man with a close-cropped black beard, bustled over to take their orders. “The Phillies, huh? Can you believe that? Fifteen years it takes them to get back into the Series.”

“It’s the damnedest thing,” Paul said. “I thought the Dodgers would nail them, but no such thing.”

“Yeah,” said the bartender, wiping his neatly manicured hands on a clean linen cloth. “Well, goes to show ya.” He smiled broadly at Violet. “I haven't got your name. Seen you in here a few times with this jack-off and Deb, though, I think.”

“Yeah,” she said quietly. “I'm Violet Meldon.” She took his proffered hand lightly. His grip was firm and quick.

“She's visiting from Providence,” said Paul, leaning over the bar.

“I'm Bobby Landau,” said the bartender. “Call you Vi?”

“Sure.”

“Okay, Vi, what are you drinking?”

“Vodka Collins, please,” she said.

“We can do that,” said Bobby. “What’ll it be? Goose, Ketel One, Beefeater…?”

Judy smacked one of the men on the shoulder as he made some comment to her.

“Gray Goose will do,” she replied. “Thanks.”

“No problem,” said Bobby, scanning the customers. “Coming up.” He swiftly prepared her drink, set it down in front of her, and moved off down the bar toward a middle-aged man waving an empty shot glass in the air. Looking back over his shoulder, Bobby said, “Let me know when you need another.”

Violet sipped her drink. It was a good one. She quickly finished half of it, then sighed and stared up at the TV. The talking heads bored her; she cared little for sports other than baseball, and even then, only if the Red Sox were playing. Calder had been the sports fan. Left undisturbed, he could watch these shows for hours. “What?” she asked, startled to hear Paul say something.

“I said, are you all right? You sort of drifted away there.”

“I'm fine…you know.” She shrugged. “I'm all right.”

“You look tired.”

Violet sighed, wishing she were back in the house with Deb. The idea of a drink had been appealing, but she didn't want to talk about personal matters in a bar full of strangers. She wished Paul would talk to Bobby instead. “I am tired,” she said. “Don’t feel like talking.” She finished her drink. “Tell me about the leopards or something.”

His eyes brightened. “Well,” he began, “you’ve probably—”

“No!” shouted Judy. Violet, having forgotten about her, turned at the sound of her voice.

Judy’s boyfriend slouched on his bar stool, his head drooping, one arm raised in a weak gesture of defense, defiance, or dismissal.

Judy stood beside him, legs wide apart, fists clenched, her face angry.

“Don't you ever say that!” she shouted at him. Violet thought that Judy might reach out and shake him.

“What the hell?” Paul exclaimed.

Bobby, calmly polishing a glass, wandered over to stand opposite. “They've been in here drinking since ten this morning,” he said, unhurriedly placing the glass down and picking up another. “He works nights at Walmart, so he drinks during the day and sobers up for his shift later. Kind of late for that now, so he must have the night off. She’s an actress, so she’d usually unemployed. This happens all the time…they get drunk, they get into a fight. Mostly just on weekends, though.”

“Oh yeah?” asked Violet, casting a contemptuous glance at the couple.

“She just does it to show off her chest,” Bobby said, while rapidly and expertly creating another vodka Collins for her. “Typical behavior.”

“What are they fighting about?” Violet asked, feeling obligated to converse in payment for the drink; Bobby had waved away her cash.

Before the small barkeep could answer, the dispute escalated. In her peripheral vision, Violet saw movement: Judy's arm swinging. Layered with her dark, solid mass, the arm was large and muscular. Her hand smacked into the side of Gerry’s face, knocking his glasses spinning to the floor. He reeled from the impact, almost toppling from the stool.

He said something indistinct, but Violet caught its whining tone. She snapped, “Now you stop that. Don't you go saying that! I hate it when you say that!” She feinted at Gerry, and he flinched. He mumbled something that Violet couldn't hear, in the babble now rising to distract the embattled couple. Several patrons gathered around them, obscuring Violet's view.

“He's always saying how no-good he is, how he's never gonna be anything at all!” yelled Judy, turning to one person after another, taking steps this way and that. Tears were running down her face. “It's not true, it's not true!” She was almost wailing.

“I'm clueless, here,” remarked Violet. Somehow half her second drink had disappeared.

“Hah?” said Paul, glancing at her. Bobby leaned on the bar in front of her. He spoke confidentially. “Very high drama content there,” he said. “They live together, and they come in here almost every day. Aside from working at Walmart Gerry writes poetry on the side; publishes some every so often. She's an actress, like I said, gets the occasional part at Long Wharf, community theater, what have you. Very high emotional levels between the two of ’em, see? And the fact is—” Here, Bobby leaned even closer to her. His teeth came together in an even line, and he said, “They love to fight, to do this in public. I think it's childish, myself, but I'm a bartender, and I'm supposed to be able to relate in one way or another to everyone’s emotional outbursts.”

“And a bar is a good place for an emotional outburst,” Paul observed.

Bobby laughed, an explosive syllable of hilarity. “I'll have to see if I can calm them down a bit before they really get into it. They're pretty well primed.” He moved off down the bar, ostensibly to service an elderly customer who was ignoring the histrionics directly behind him.

As Bobby filled the old man's mug with frothing beer, expertly cutting off the tap stream before it could overflow, he spoke quickly and quietly to Judy and Gerry. Judy listened and nodded, wiping her eyes every so often. Gerry, a thin academic type with a sparse goatee and long lank hair, ignored Bobby, concentrating instead on his drink.

“Why not take it outside, then, if you're gonna get physical?” Violet heard Bobby say. To Paul she said, “I'll bet that Judy can throw a good punch. She's no small person.”

“Yeah, I'd hate to—”

The smack of fist meeting flesh echoed off the mirror. Violet turned in time to see Gerry fold up and slowly collapse onto the floor, one clawed hand still hanging onto the seat of the stool. Judy was cocking her fist to deliver another blow, hollering, “No no no no!” Gerry clambered to his hands and knees as she stood there with her legs spread far apart. She leaned over him, her big breasts swinging inside her sweater. Gerry mumbled something at the top of his voice.

She aimed a kick at him. “Aw, she isn't…” began Violet as three patrons grabbed Judy, preventing her from further assaulting Gerry.

“That's it!” shouted Bobby, standing on tiptoe behind the bar. “Outside!” he added, flinging his arm in the direction of the door. “Dammit, you two get out of here until you learn how to behave!” Judy tearfully stalked out. Two bored-looking barflies assisted the staggering Gerry. The sound of Judy's voice trailed behind her as she descended the steps and grew flat as she exited into the deepening evening. Bobby came out from behind the bar and followed the group down a few stairs to make sure that they were indeed going to stay out on the sidewalk. Then he went back inside. After freshening a drink or two and exchanging comments with the patrons, he came over to Paul and Violet.

“Really,” he said, clearly annoyed, “those two are too much. I think that they're together 'cause they’re the only ones who can stand each other.” He sighed deeply. “She swears that she's gonna press charges on him…says he hit her. He's so drunk he doesn't know what's happening. The fact is, they'll keep this up outside, till someone around here calls the cops.” He shook his head. “It's a real traffic-stopper. They love screwing up this intersection.”

“And they live together,” Violet stated. She was feeling a little better after two drinks and didn't refuse Paul's offer to buy her a third. “Why wouldn't, why doesn't she just leave him alone, or try to help him?” she asked Bobby.

“It's the way they show each other that they care. If they didn't fight all the time, they'd go crazy. Or at least that's what Gerry told me, once,” Bobby said. “He says that it keeps their nerves at peak performance, keeps them alive and vital.”

“Vital, no less,” supplied Paul. His voice was a little slurred, after three beers.

“Well, I don't know, right? Poets, actresses…who knows?” asked Bobby. “Rhetorically speaking, that is.”

“I don’t know,” said Violet, whose head had begun buzzing from the alcohol. The familiar feeling had once formed an extensive backdrop to her life; dimly she understood that she was approaching dangerous territory by drinking. “I don’t understand what some people see in each other.”

“I hear that,” said Paul. “That was sort of how we felt about you and Cal.” He never called Calder anything other than Cal.

Violet frowned. “You never liked him,” she said, somewhat accusingly.

Paul didn’t bother to deny it. “We just thought he was always bossing you around, telling you what to do. You hardly ever seemed to have an opinion of your own when you were with him. Plus, he always knew everything about whatever we were talking about. Even when he didn’t know a damn thing.” He shrugged and drained his mug. “People like that annoy me.”

Violet smiled to herself. Calder, who hated being called Cal, hadn’t liked Paul any better than Paul liked him. It was one reason why Violet’s friendship with the couple had been somewhat in remission during her marriage. Also—she hated to admit this to herself—Calder’s interest in Deb had never seemed entirely motivated by mere friendship, not that anything had ever come of it.

A longhaired young man standing at one of the bar’s windows said, “Oop. He slapped her.” Several people turned, at this remark. “Christ,” added the fellow with some delight in his voice. “He’ll pay for that!”

Other patrons got up to watch. “Now he'll get himself killed if he doesn't get out of the street,” one said to the longhaired guy.

“What's she doing?” asked someone else watching the dispute. “That's the police call box!”

“Jesus. She’s calling it in!”

“Oh no,” said Bobby. He hurriedly dried his hands, asked one of the customers to tend bar, and trotted downstairs.

As Violet methodically drank her vodka Collins, she heard an approaching siren. Flickers of red light scattered across the dimness of the bar's interior, catching interesting reflections from the ranked bottles. After a moment or two a flickering blue light joined the red one. The siren died suddenly.

Paul got up and walked to the head of the stairs, saying, “We might as well be getting back. Supper should be just about ready.” She stood, a little surprised at the blurriness of her vision, and followed him down the length of rubber-treaded stairs, holding on to the handrail.

Parked at the side of the building, their lights sparkling brightly amid the twinkle of cars at the intersection, stood a police cruiser and an emergency vehicle. Several men in varying uniforms stood around in a small group looking alternately bored and aggravated. At the approximate center of this group stood the soused lovers. Gerry seemed more sober than he had in the bar, but Judy was no less distraught. A cop patiently took down her statement. She stood with her head thrust aggressively forward, talking loudly in a voice thorny with righteous indignation. Violet heard her demand to be taken to the hospital emergency room for an examination.

The EMTs were trying to talk her out of it as Violet and Paul passed by.

“Are they both actors?” Violet asked him as they stood waiting to cross the street.

He laughed. “Only when they've got an audience.” He took her arm as the light changed. “Let's get out of here before they start asking for witnesses. You ever have any fights like that with Cal?”

“No…nothing. We’ve fought a lot more since we split up. You think maybe fights define love? I mean, how low you go…does that tell you how high you can go in the, you know the other way?”

“Did you say something?” he asked her as they made the opposite curb. “I was watching the traffic—didn't hear you.”

“Talking to myself,” she said. “Mumbled, actually. You know, I’m sort of drunk.”

“I'm not surprised, with all that vodka in you. Let's get a little food in there, too, huh?”

“Yeah.” They walked a few steps in silence. She said, “That fight…those two…they're always like that?”

“Never changes,” Paul said. “You think I got animals in the zoo to deal with.” He laughed. “They're actually fun to be around when they're sober.”

“When's that?”

“Periodically.”

At least there isn’t anything hidden about that relationship, Violet thought. The whole thing is on display. From the outside, everything about her marriage had looked healthy. Even from the inside it was generally quite good, if unexciting after a point. The point, and she knew this, had known it for years, was Jessie. After his birth, sex went out the door for a walk and got lost. She was still pondering this when she entered the kitchen where Deb was finishing up dinner. In addition to sweet and sour pork and egg rolls, she had made egg-drop soup. Violet stared at the tray of egg rolls and the wok full of steaming pork and vegetables. “You amaze me,” she said to Deb.

“Oh?” Deb, in long skirt and apron, gray eyes soft behind her glasses, was physically everything Violet would have liked, at times, to be: slender, graceful, attractive. Deb, always at ease with herself, took her good looks for granted, never wore much make-up, and had no pretensions toward glamour. Men liked her, and at 35 she still attracted admiring glances in stores and on the street.

Deb laughed while putting the egg rolls into a shallow serving bowl. “Here's the gal taking a solo motorcycle trip down to Virginia telling me that I amaze her,” she said to Paul.

They ate in the kitchen. The good food and the warmth combined with the alcohol in her blood made Violet sleepy. She found herself staring at the spice rack Calder had made for Deb's Christmas present two years previously. Paul and Deb did most of the talking. Violet resisted being drawn into conversation, although she knew that she was being antisocial.

“You're not adding much,” Paul said after a while.

“Don't have much to add,” she responded. “I’m just fried after the ride.”

“Well, I can understand that.”

“Listen, you know, I never knew you didn’t like Calder,” Violet said.

Deb gave Paula a sharp glance. He held up both hands, palms toward her. “Hey, we were just talking,” he said to his wife, a trifle defensively. “I figured I could say it now, them being divorced and all.”

Violet looked at Deb. “He never came on to you or anything, did he?”

Deb looked uncomfortable. She shifted in her chair. “Well, no…”

“That doesn’t sound definitive,” Violet said.

“He sort of accidentally copped a feel off her once,” Paul said, frowning.

“That was just an accident,” said Deb. “Three summers ago, when we stopped by to visit you on our way up to Maine, I was coming down from the bathroom when I stumbled over that loose stair tread.”

“Yeah, it took him forever to fix it, such a small job.”

“Anyway, he was at the bottom of the stairs and when I tripped he more or less caught me. You know, it was suddenly, and you can’t choose your grip when an accident happens.”

Paul snorted. “You said it took him longer than necessary to let you go.”

“It wasn’t that big a deal,” Deb said. “It wasn’t like he groped me or hit on me or anything.”

“Anyway, it’s old business,” said Paul, a little shortly, grasping a morsel of pork with his chopsticks. They ate in silence for a few moments.

“I suppose Calder took all his plants,” Deb said at last.

“He wouldn’t have left them with me, that’s for sure,” Violet said. “I would have let the damn things die. My black thumb, you know.” She snorted. “What's-her-name has a bunch of plants, too.”

“Who, Maureen?”

“Yeah, her. So he and Maureen can start their own stupid jungle,” Violet said. She knew that she was losing control but was too drunk to care. “I sound pretty bitter don't I. Well, I don't mean to. No, I do mean to.” She blinked. “Oh…” Suddenly ashamed of herself, she got up and went into the living room. Paul and Deb stayed behind to clear away the dishes. Violet heard them talking in low voices. Not wanting to hear their words, she turned on the TV.

As it came on, she glanced up at the painting on the wall above the set. It was a Christmas present from Paul's sister, an artist living in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Violet had never liked it. It was large, almost two feet by three feet. Its subject matter was a matter of conjecture, in Violet’s view: a yellow squiggle winding among simple geometric shapes: squares, triangles, rhomboids. Other shapes in cool greens and blues were more organic in that they had no regular boundaries or patterns to their order.

To Violet, the painting looked like something done by a five-year-old. Her own taste in pictures ran to Impressionist landscapes or Andrew Wyeth.

Violet picked up the remote control and began channel surfing. The many political offerings reflected the upcoming presidential election. One state, two state, red state, blue state, she thought, and smiled. The pundits were out in force, spinning, opining, and holding forth. Who’s better for the country? Who’s better for the world? Who would lead the nation out of economic chaos?

Violet worried about unemployment. When so many experienced people were losing their jobs, how was a former housewife who had only ever worked as a waitress supposed to function in the marketplace? She hadn’t used a computer for anything other than netsurfing in years, knew no word processing or how to manipulate spreadsheets, had messed around with Calder’s copy of Photoshop but still didn’t know the difference between a jpeg or a gif, couldn’t write HTML or any real programming language, didn’t know what the hell Ruby on Rails was or Joomla or JavaScript or CSS or PHP, couldn’t edit video…A prospective employer would take one look at her pitiful resume and move on to more qualified applicants.

And these days, even over-qualified ones weren’t getting in the door anymore.

She switched channels, not wanting to see more bad news. She found an old Peter Sellers film and sat down to watch for a while. Feeling warm, she pulled off her heavy sweater and settled back in the chair, ignoring the painting over the TV set.

“You want something to drink?” Paul asked, sticking his head into the room.

“I better not,” Violet said after considering the offer for a moment. “I would actually like one, but you might end up having to prevent me from running out to smash car windows or something.”

“Ummm. Sex is better than violence,” he said, grinning.

“I wouldn't know.” She stared at the TV. A few minutes later Deb came out of the kitchen and sat down on the couch next to her.

“Hi,” said the small woman. “You feeling okay?”

“Loaded, exhausted, otherwise…meh!” said Violet.

“Want to talk at all?”

“I'm sort of talked out. I say stuff over and over and the words get pretty thin and even I can’t hear any meaning in them…so how could you?”

“I've never heard you sound this way,” said Deb. “You’re worrying me a little.”

“You just never saw me this drunk.”

“Oh, I don’t know…I can remember a few times…”

Violet smiled. “Yeah, well, I’ve toned that down a bit.” She cast a rueful grin at her friend. “Though maybe not today, so much. First time in quite a while. What with the divorce and all.”

“I think you've changed, some,” said Deb quietly.

“I'm entitled. But I don't think I have. I mean, everything else has changed, but I’m still the same. Maybe that's the problem.”

“You're not being fair to yourself.”

“Fair? I don’t know what’s fair. Is it fair that I should lose my husband, my son, my house? Is it fair that I don’t feel happy anymore?”

“That will come, you know. There are other men in the world.”

“I don't know if I want any. I don't know if any want me. You know, Calder and I hadn't had any sex for almost six months before he told me he wanted to separate.”

“You never told me that,” said Deb after a pause.

“I wouldn't tell you now if I wasn't drunk. I didn't want to face it. He didn't want me, and I didn't want him. I thought it was just a lull, or something…then he tells me that he's fallen in love with this Maureen.” She couldn’t have injected more scorn into the name.

“He was attracted to you, though, wasn't he?”

“In the beginning, yeah, sure. Three, four times a week or more. But you know what he said to me? After we were divorced? He said he loved me when we were married, but he wasn't in love with me. The infatuation thing, I guess. And sex. That’s what sex does, it blinds you to reality. Everything’s glowing. Wow, let’s do it! Oh, I love you! Then, wait a minute—who the hell is this I’ve been screwing for six months? Then he falls in love, but with Maureen, and couldn't keep our marriage going.”

“I'm sorry, Vi,” said Deb, putting her hand on Violet's arm.

“Thanks. I do appreciate you. But I don't know what I'm going to do. I haven't got a career or anything. I can't keep Jessie because I can't afford to.

“See,” she said, sitting up, “the one thing is, I've never been alone, really. There's always been someone to talk to. But now, I really need to be alone to talk to myself for once. And I don’t know how to do it, not really. Which is why I'm taking this backpacking trek into the Shenandoah National Park.”

“It rains a lot in the mountains this time of year,” said Paul, who entered the room while she was speaking. “You could get soaked. I mean, how much camping have you done?”

“Enough,” she said, avoiding his gaze. “In any case, it’ll be warm enough in the hollows, no wind down there. There’ll be plenty of shelter if I stay off ridges during storms.” Suddenly she belched. “Oh, excuse me!”

“You can stay here for a couple of days, if you like.”

“Thanks, Paul,” Violet said. “And no offense to you guys but it's not what I need. It would be easy…but I have to do the hard thing now.” She stifled another belch. “Ooh, the hard thing will be to get to bed without killing myself. I'm going to say goodnight.” She stood and, after hugging her friends, walked carefully out of the room and upstairs to the second floor, where her bags were, in the spare room at the front of the house.

The open curtains let in illumination from a lamppost across the street, enough that she didn’t need to put on the overhead light as she pulled her nightgown out of her backpack. Then she drew the curtains shut and undressed. After slipping her crucifix over her head Violet sat down on the edge of the bed.

The room spun slowly around her. She knew she'd be sick if she closed her eyes, so she lay down and resolutely stared at the windows until she lost consciousness.

Voices from outside woke her. Morning light filled the room. She rolled over onto her back, staring blearily at the ceiling while checking for hangover symptoms. Her stomach felt all right, but her head—!

The voices outside were those of children, pitched high with excitement. She rose slowly, letting the cool air of the room wake her. Scratching her chest between her breasts, she headed for the bathroom down the hall. The house was quiet, with no odor of breakfast. On her way to the john, she passed Deb and Paul’s room. Through the open door she saw the room was empty.

After a long hot shower, she slowly dried herself off, listening to the persistent cries of the children from the street. She looked at herself in the misted mirror. Eyes a bit bloodshot, eyelids swollen and puffy.

The reality of the day had been slowly filtering in. Today she would visit her parents, then head out on the last leg of her trip down to Virginia. Vague excitement tried to shoulder past her headache but needed tea to fully push into her awareness. Donning a tee shirt and jeans she went downstairs to see about fetching some.

On the kitchen table was a hand-written note from Deb saying that she and Paul had gone out to purchase some things for breakfast. Violet turned drew a kettle of water and set about preparing a cup of tea.

As she sat at the kitchen table drinking it, willing her headache to recede, her friends came in the front door.

“Good morning,” said Deb, entering the kitchen. “How are you?”

“Slightly hungover,” Violet said, attempting a mild grin.

“Want something, aspirin, maybe?” Deb asked.

“No, just some breakfast. I can make it myself.”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” Deb told her. “You’re a guest, and a hungover one at that.” She placed a large white paper bag on the table. “Croissants, Danish, bagels…you name it.”

“Ooh, this works,” said Violet, pawing an “everything” bagel out of the bag.

“You’re a better man than I am,” Paul said, retrieving a can of coffee from a cabinet.

“That was never in question,” Violet replied with a grin. She watched Paul pour water into the coffee maker. “The best thing for a hangover,” she said, “is a hot shower and a big meal, and maybe a little exercise. Calder taught me that.”

“Calder is a dipshit. It wouldn't have helped any hangover I ever had,” Paul said. He sat down across the table from her and leaned back to watch coffee dripping into the carafe.

“Eggs?” asked Deb, holding up a carton.

“Over easy,” replied Violet. “It wasn’t that he drank a lot,” she went on, “like all the time. But once or twice a year he would get dah-runk at a party or something. The next morning he’d do some push-ups, take a hot shower, and have some bacon and eggs.”

“Craziness,” Paul said. His eyes followed Deb as she made coffee. Violet watched his gaze stray down Deb's slim back and over her ass. She sighed.

“I used to think so, too,” Violet said, “until I actually saw him do it. And an hour or so after eating, maybe after taking a walk, he'd be more or less human again. Quieter than usual, but functional.”

“I guess it's a method that runs in the family,” Paul said, then winced. “Uh, sorry—I didn’t, uh, that is…” He bit his lips. “Balls.”

Violet waved a hand. “Forget it,” she said. “I’m not feeling well enough to feel bad about references to my ex.” She sipped at her tea. “I’ll have a cup of coffee, too, Deb, if there’s enough.”

“Sure. That’s right; you always have a cup of tea first, then coffee for the rest of the day.”

“Yeah. Listen, sorry about the rant, last night.”

“It was hardly a rant,” Deb said, smiling at her. She cracked an egg into the large cast-iron frying pan in which butter sizzled.

Paul had pulled a small portion of his beard into his mouth and was chewing on it. There was a small but noticeable gap amid the hair on the left side of his chin.

“You know, you can still stay here for a few days if you like,” he said. “We've got the room up there, and there are movies in town, places to go…Bridgeport’s actually got a couple of good museums these days. The old mall was converted into a community college, and they always have a good art show there.”

But Violet was shaking her head. “I can’t stay here and be a depression-sink,” she said. “I’m going to be depressed anywhere in a town, or a city. Trees and air would do me good.”

“Is it that a moving target is harder to hit?” asked Paul, cocking his head to one side.

“PK,” began Deb, a warning note in her voice.

“It’s okay,” said Violet. “It’s okay. That's what I need…no breaks. Just treat me the same as any other time. I know you feel sorry for me. I feel sorry for me. I'm sick of it. I want to start feeling good about things again, and this is the only way I can think of to do that.”

There was silence in the kitchen as Deb poured coffee for the three of them.

Deb sat down next to her and said, “You're right. What I want to do is put my arms around you and hug the hell out of you, and cry with you.”

“Oh, I'm cried out,” Violet said, looking down into the cup. “Mostly.” She reached absently into the right breast pocket of her shirt and pulled out a cigarette, then laid it on the table after remembering her hosts did not smoke. “Crying empties me, and I need to be filled. I just don't know what with, yet.”

“Not alcohol,” said Deb quietly.

“It helps.” Violet couldn't look her friend in the eyes.

“Damn, I'm really on the spot here, aren't I?” Deb asked Paul. She reached out touched Violet's arm. “I care about you; I care what you feel and what you think. And you can't drink all this—'” she waved her arm around in a vague, all-inclusive gesture, “—away, out of your life. If you think you can, you're kidding yourself.”

“You sound like my mother,” Violet mumbled. “She always tells me I refuse to face issues squarely. I do the best I can!” She stared angrily at her friends. “What I want, more than anything, is to be by myself. I need to know what's inside me. I have to get loose in there somehow.”

“I remember when you came back from California,” Deb said. “As a Jesus freak.”

Violet smiled as she automatically raised a hand to touch the crucifix under her shirt. She turned the movement into a scratch at her neck. “Maybe I overdid it, but still, religion helped me through a bad time. It was better than taking all those drugs, wasn't it?”

“Maybe you should go back to the church, then,” said Paul.

“No,” said Violet. “Back then I did have the faith that Someone was listening to me. I don't really believe that anymore. No one is listening, no one cares.”

“That's not true,” said Deb.

“I just mean there's no God out there. If there's anything, it’s inside. And inside me there’s nothing right now.”

“How can you say that?” Deb asked.

“Maybe you don't know me as well as you think you do,” Violet said, and stood up. She drained her coffee cup while her friends sat in silence. She knew she’d hurt them and was ashamed of herself but couldn’t think what to say to retract the barb. Instead, she went upstairs to gather her things.

Paul helped her bring her bags out to the motorcycle and strap them on. “Thanks,” Violet said, hugging him. “I'll send you a raccoon or something from the Great Woods.”

“No need. I get enough of that at the zoo,” said Paul. “Kids hauling dead budgies in, or sick chameleons or some such.”

“Shop talk,” said Deb, standing next to her husband. She hugged Violet as well, then they watched as she wheeled the motorcycle out of the garage. “Say hi to your folks for me,” said Deb.

“I'll do that,” Violet replied, putting on her helmet. She knocked the kickstand back into place and straddled the machine before pulling on her gloves. “Look,” she said from inside the helmet, groping for an apology, “I would rather just cry, because it's easier. But I'm afraid. It's like…well, it's like, here I am, thinking I was all done with growing up. But now I have to keep on with it. It isn’t fair, you know?” The tears were coming…she blinked them back. Knock it off, frigging crybaby, she told herself angrily.

“It works out,” said Paul.

“Maybe. Maybe not,” Violet replied. “I'll call you when I get back from Virginia. Enjoy the Poodle Boys.” She started the bike, jazzed the throttle and, with a wave to her friends, engaged the clutch. The bike crunched slowly down the drive and into the street.

Weekend traffic buzzed through the intersection, but she didn't care. Her mind was dull and gray. The residual effects of the hangover made her head feel like a lump of lead.

The day, on the other hand, was fine for traveling, a beautiful Saturday morning in Indian Summer. North of the intersection she picked up speed.

Violet was used to being stared at when she rode the motorcycle. On familiar roads, in and around Providence, she used less concentration while driving, so she usually didn’t notice if other motorists reacted to the sight of a woman riding a big bike. While threading her way through the streets of Bridgeport, however, she had to be more alert and observant. She saw drivers in oncoming cars. Some smiled, or waved, some pointed or made remarks to their passengers. One youth flipped her the bird, scowling, when she pulled around him at a traffic light. She ignored all distractions, aware that she felt hidden behind her crash helmet mask and leather jacket costume.

Concentrating on the unfamiliar roads north of Bridgeport she had not been able to enjoy the weather. Once she left the urban crush behind, she tried to think less of her anger and frustration and more of the trees.

The countryside reminded her of her home outside of Providence. The autumn foliage was lovely, but the memory brought pain…she would never see that home again.

Concentrate! she told herself angrily. Colors were okay; she let them fill her mind with smears and blurs in a sort of self-hypnotic process. The further north she rode toward Danbury, where her parents lived, the fewer—and older—were the houses along Route 25. Shopping centers, large and modern near Bridgeport, dwindled to storefronts and occasional drive-in restaurants, some of which she remembered from her pre-teen years. It seemed to her that at any minute she would see the cars owned by her high school friends pull into the lots, full of shouting, laughing teens. As always when she returned home, she was surprised to see these small establishments still in business. Some, indeed, now bore FOR SALE signs or were boarded up: clear indications of the faltering national economy.

In the drone of the motorcycle's engine and the racing of the wind she heard nothing save for a tune running through her head, an old song by Carly Simon, about moving in together because there wasn’t anything else to do. Wasn’t there a Stones song like that, too; something from Flowers, maybe, or Between the Buttons? She’d always been a Stones fan. She pulled over, slid a compilation CD Calder burned for her into the bike’s player, and rode on with the music blasting up at her from the speaker. Fine as it was, it couldn’t dispel her blues.

Both Mick and Carly had sung about being lost, hoping to find some fulfillment in marriage. Well, that was the way it was supposed to be.

But marriage, maybe, wasn't right for high school kids in hotdog stands.

Go on, go on, she said to herself and the road. Yes, but why? Can I be married again?

And children? She had Jessie—but he lived in Boston with Calder and Maureen.