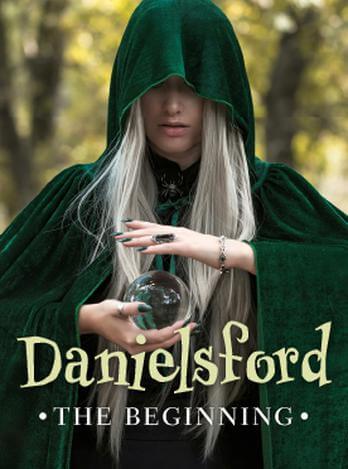

Danielsford: The Beginning

Synopsis

Mary Bradbury survived being hung for Witchcraft and Sorcery in 1693 Danielsford, Massachusetts Bay Colony. But at the moment of her death, she "took the path" and traveled to the year 2020. Now, centuries after her "death," Mary will tell the story of her life, how she came to Danielsford, and what happened that caused her to be hanged a year after the Salem Witch Trials ended. As she weaves her tale, she sheds light on the transformation of Rebecca Collins from close friend to malevolent force of evil. And she reveals how the paranormal struggle that began in the time of the Salem Witch Trials might be ended once and for all.

Danielsford: The Beginning Free Chapters

Prologue | Danielsford: The Beginning

↓

Mary Bradbury stood, staring out into the street. It was a warm summer afternoon, and she felt the heat through the screen door. After a minute, she closed the inside door and walked to a sofa. She stood for a moment, then nodded and sat.

Across the room, Frank Jackson, her fiancé, lounged in his easy chair and watched. Their house guest and close friend, Marjorie Putnam, sat at one end of the sofa, waiting.

Mary glanced at Marjorie, who nodded. She took a deep breath and turned to Frank. “I told you when the time was right, I would tell you about myself.”

“I remember,” he said.

“It is time you know me, who I am, and where I came from. Try to be still and not interrupt, for a change.” She took another breath and began telling her story. “I will start at the end and then go to the beginning.”

At 4 PM, Mary Bradbury, 29 years old and single, stood beneath a tall maple tree on Danielsford’s Town Common with her hands tied tight behind her back. She wore a drab, ragged brown dress that hung loose and formless. The authorities took her usual clothing after the arrest.

She glanced upward and saw, a foot above her head, the thick hemp rope. At the end was a noose, hanging motionless in the still air. The rope looped over a stout limb a few feet above her and then down to wrap once around the tree trunk. Three men held the other end.

The man responsible for her execution, William Underwood, stood beside her. Next to him was her chief accuser, Thomas Walcott. He looked pleased that his allegations had at last borne fruit. Looking upset, Constable Eaton stood by himself six feet away.

Most of those living in Danielsford gathered around the tree. She recognized all of them. The women frequented her shop and bought her potions, elixirs, tonics, and poultices.

The majority looked sad, although she saw a few were eager for the spectacle to begin. Their eyes gleamed at the thought of seeing her die at the end of the rope.

A court found her guilty of sorcery and murder, and they sentenced her to death a week earlier in Ipswich. Worse, they held the trial without giving her a genuine opportunity to present a defense. Yet, it was considered a lawful trial, with judges appointed by the Royal Governor.

The witch trials in Salem Town were over many months earlier. It was now 1693, and people were becoming enlightened. It couldn't be happening, yet it was.

“Mary Bradbury,” said William Underwood. “You have been charged and found guilty of murder, and practicing Witchcraft and sorcery. The sentence is death by hanging.”

“They did not allow me a defense,” she replied. “You know I am innocent of such charges.”

William stared into her eyes. In his, she saw sadness. He was a good man, and his wife a fine Bible believing woman.

He reached up and pulled the noose lower. Then he took a dark cloth sack and began slipping it over her head. She jerked away.

“I am not permitted a final word?” she asked.

“Aye, Mary.” He stepped back. “Say thy last.”

She turned to the crowd. For a few seconds she let her eyes wander from one person to the next. When she spoke, her voice was solemn and accusing.

"I am innocent of these charges.

I curse this town and all I see.

Three and three, so shall it be.

You shall not rest 'til I have mine,

If it mean to the end of time.

Three years and three days shall be your way."

She turned back to William Underwood and nodded. He slid the sack over her head and fitted the noose around her neck. After adjusting the loop, he turned and motioned to the three men.

They took the slack in the rope and pulled hard. Mary raised skyward a foot. Her legs kicked and her body jerked as it fought for air. Tensing and struggling, she rocked back and forth at the end of the rope, fighting to live. In time, her struggles lessened and then stopped.

She made no sound. There were no cries. Air could not get in; neither could the air in her lungs get out.

Thomas Walcott, her accuser, stepped close, uncertain what to do. He had seen no one hanged.

“I think she is passed,” Constable Peter Eaton said.

“Leave her,” Walcott said. “I must be assured of her death.”

The men moved to the tree trunk and tied off their end of the rope. Mary hung, her head drooping toward her chest.

Underwood eyed the limp figure swaying gently in the light breeze a foot off the ground. He looked at Walcott and saw his satisfaction.

You won, William thought. But I fear you have brought something else upon us.

Almost a year earlier, Thomas Walcott charged Mary with sorcery and consorting with the devil. Constable Peter Eaton arrested her, and she spent a full day answering questions posed by Eaton, Walcott, and Reverend Churchill.

According to Eaton, who spoke of Mary's examination with Underwood, she had answered every question to his satisfaction. Reverend Churchill admitted that she said the Lord's Prayer better than he could recite it. After discussion, they released her with no charges.

Walcott opposed the release, telling them it was more of her sorcery. The devil deluded them, making them hear what she wanted them to hear. Reverend Churchill, being a minister and a man of God, could not accept the explanation.

“She is a Bible woman, Thomas,” he said. “I believe not she is a witch.”

“Look in her shop,” Walcott countered. “The potions are of Satan. So be her elixirs.”

“I have looked,” the minister countered. “My wife trades with her. So does yours. Are our wives witches?”

Walcott snorted, rose, and walked from the room. Reverend Churchill watched him go. He frowned.

“This will not be the end,” he said to himself. For the next year, Walcott refused to speak to Mary or be near her, even in church.

Two minutes passed as Thomas Walcott eyed the hanging woman. Satisfied, he nodded.

“I think she can now be taken down,” he said.

Underwood motioned to the men. They lowered the lifeless body to the ground. He removed the sack and looked at Mary's face. William Underwood was familiar with hangings, and death was no stranger to him. Mary Bradbury was dead.

He gestured to a nearby cart. “Put her in the wagon and take her into the forest. Make sure she lies somewhere that animals will not disturb her. She may not be permitted to rest in our cemetery, but her body deserves not such an end.”

“We shall bury her,” one man said. “She should have a burial.”

“No,” Walcott said. “Waste not your time or honest sweat with a burial. She is a sorceress.”

The three men glanced at one another. Walcott’s order did not sit well. They removed the noose, untied her wrists, and carried her to the nearby wagon.

“She shall be buried if I must do it alone,” one man whispered as they lay the body in the wagon bed.

The others agreed. They drove a short distance out of town, to a trail just wide enough for the cart. In late afternoon, with darkness approaching, the forest was a strange, dark place inhabited by frightening, terrible creatures. They discussed where to put her body and followed the narrow path for a minute before stopping at a spot that looked suitable.

The men spent a few minutes digging a shallow grave. When finished, they lay Mary Bradbury in the hole and covered her. They then found several logs and placed them atop the grave to keep animals from digging up the body.

“I think she is not a witch,” said another.

“Walcott accused her when Perkins died,” the second man said. “He testified of her selling an elixir that hastened his death.”

“Believe it not,” said the first. “Mark my words. It was Rebecca Collins what killed Perkins.”

“I did hear as well that Walcott wished Mary’s building.”

“He will have the house now, should he want it,” said the third man. He looked at the grave. “What think you of the curse she spoke?”

The men glanced at each other and shook their heads.

“It made no sense,” the second said. “Would a Christian woman say such?”

“One unjustly convicted,” the first said. “Yes.”

“Come. It grows dark. This area is not to my liking. There is evil afoot all about us. Let us return.”

They spent a few more seconds at the grave and left.

Two days after her burial in the dark forest, the man who drove Mary to her grave brought several residents to the spot. They had with them a rough fashioned coffin.

When they uncovered her, they found that death had not changed Mary. She lay as if she they had put her there only minutes before.

“This cannot be,” Harold Avery said.

“Perhaps it wise to leave her. This surely be Witchcraft,” another warned.

“She is not a witch,” Avery said. “They have found the true witch out. Help us get her in the box.”

The men lifted Mary into the coffin and started for town, a half-mile journey away.

When they arrived, they stopped at the parsonage, sitting beside the church. Avery found Reverend Churchill.

“The woman, Mary Bradbury, needs a proper burial,” he said.

“A witch cannot receive a Christian service or burial,” Churchill said.

“She is not a witch, nor is she a sorceress. Thomas Walcott falsely accused her. You know this. Rebecca Collins is the evil one.”

“Though I disagreed with the verdict and told Mary so, the high court convicted her of such. I must decline to perform the service.” Churchill’s voice was firm and final.

Harold Avery turned to the men sitting in the wagon. “Take her into the church. There she will stay until she receives a Christian burial.”

“No,” Churchill said. “A convicted sorceress may not enter my church.”

The men at the wagon hesitated, waiting for the argument to be settled.

“It does not be yours. It is ours. She was in our church every Sunday, even those times she suffered illness.”

“Harold Avery, you well know I cannot do the funeral or let her lie in our cemetery. The woman was tried and proved to be in Satan's power, though I, like you, suffered doubts.”

Avery motioned the men to place the coffin in the church. “There it will remain until you do justice, sir.”

Reverend Churchill watched, powerless, as the four men carried the coffin inside. He followed and scowled as they placed it on the long table serving as the altar. It was the last time Churchill used the church for worship. He chose an alternate location to service his flock.

Less than three years later, on a Thursday, a flood caused by a Nor’easter moving in from the Atlantic Ocean struck the town. The storm and flood water damaged every home in the village. Some residents wanted to rebuild, but most gave up and moved to other places. In the months that followed, everyone left. Over time, they forgot Danielsford, and the forest reclaimed the land.

Three years after, the town and many of the original residents reappeared, the first time occupying a small village in New Hampshire. The spectral town replaced the established village for three days before vanishing.

Three more years passed and Danielsford came to the south of Maine for three days. The appearances continued through the centuries every three years and lasted for three days.

“Three and three, so shall it be,” said a trapped villager three hundred years after Mary laid the curse. “It catches us for eternity.”

"Or until someone comes and gives her the service and burial she wishes," another answered.

"Who? Who even knows of Danielsford? Her curse destines us to come and go ‘til the end of time."

"I know not who, only that God will send someone. He knows we tried to right the wrong."

“Did we?” the other asked. “You forget, she hanged because of us.”

“We had no choice,” the second man said. “Walcott pressured us. We had to comply.”

“And sent an innocent woman to the rope. Did any of us ask God?”

“He knows all and understands. God shall relieve us of this burden in His time.”

“I hope you are right,” the first man said.

Chapter 1 | Danielsford: The Beginning

↓

The day promised to be hot. Mary Bradbury poured water into a tin basin sitting atop a small table. She took a cloth, soaked it in the room temperature water and bathed herself. Once finished, she dressed and went to find something for breakfast, settling on bread made the previous day.

After she ate, she went out the back door of her home and walked around the house to the front, where a modest room served as a shop. She sold elixirs, poultices, medicinal herbs, and she served as a midwife. There were other things as well, some of which were of concern to a few people in her village. From the day she arrived in Danielsford in 1691, her occupation had been a concern.

Despite their worries, and the claims from some that Mary was a witch, all of the women in and around Danielsford frequented her shop. They bought cures for a variety of ailments and injuries, and they called on her to treat sick family members and to birth babies.

It was too early to open. The sun had not yet risen. She worked on her stock and replenished items sold the previous day. A smaller room in back kept various herbs and other medicinal plants, and she also used it as her laboratory. There, she mixed ingredients, which she labeled and put in her store.

By sunrise, she was ready. Customers arrived early to avoid the oppressive heat and humidity of the day. She closed the shop during the hottest part of the day, reopening later for two or three hours. The temperature in the building was stifling during those hours. Fewer came in the evening, but those who did were in need of help and she wanted to be there for them.

One or two paid in coin but most could only trade food, homemade clothing, or they bartered work for her products. Money was rare in the small villages of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. She did a good business. If people thought she was a witch, they overlooked it for her talent at curing or relieving their ills.

At one o’clock, when the last customer of the morning left, she closed the front door. The heat was unbearable in the shop. Her clothing was damp with sweat. Mary wanted to find a cool place to spend the next few hours, and knew none existed.

“Mary Bradbury,” a woman said. She arrived as Mary shut the door. “Does this day be warm enough?”

“Good day, Rebecca. It is a trial. Are you in need?”

“I desire relief from the heat. Have you anything for that?”

“Would that I did,” Mary said. “I should use it.”

“Where are you off to?” Rebecca Collins asked.

“To search a place cool.”

“Should you find it, I will join you.” Rebecca laughed and continued on her way.

Mary finished closing the shop and stood, looking across the Common. There was no respite from the heat. She knew the elderly in the village suffered the most. Old people, unlike the young, were often incapable of handling the high temperatures, and she wished she had a potion or medicine to help them.

On the far side of the Common, Thomas Walcott stood with two other men. She eyed him. He had again been making accusations of sorcery against her. So far, he had not filed an official complaint.

A few miles to the south, simple accusations such as he made had led to the arrests and trials of women, and a few men all over the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The trials resulted in convictions for many. They already hung six, and dozens more awaited the gallows.

The constables went into Maine to arrest the accused, one of whom was a former minister. The young girls making most of the charges had not visited Danielsford. Mary hoped they stayed away.

Walcott began accusing her of Witchcraft months earlier. So far, with nothing being in writing, the officials in the village seemed to ignore him. No one came to arrest her and, she hoped, everyone forgot the accusation.

While she ran her store, she kept her ears open. It was a dangerous time to live in the Bay Colony. Claiming a person guilty of sorcery took but a single written statement.

Why town officials did not act puzzled her, but she refused to dwell on it. She wondered whether the women of the village played a part.

Most of those coming to her were women. They ran the home, cared for the sick, and bandaged the wounds. They knew her poultices, elixirs and tonics worked. Without her cures, Danielsford would be a fearful place to live. Injuries and illnesses were all too common. She left the shop, going around the building to her home, where she settled at her table with bread freshly baked the day before.

After eating her fill, she went to a shady spot in the small backyard and sat leaning against the trunk of an old oak tree. It was only a little cooler in the shade, but preferable to the suffocating heat of her home and shop.

From her position she could still see onto the Common. Walcott was there, still talking to the men. She watched for a few minutes and dozed. Before long she slept, her back against the tree.

When she awoke, the sun was low in the west, though hidden by the tall trees she could not see it. Mary rose and stretched, noticing that the temperature had not dropped much, if at all.

She went to the shop, determined to spend the evening hours there. One or two customers always came later with an emergency. Some were injuries, others illness. They, most often the women, were sometimes desperate for her help. Mary never complained, even in the middle of the night.

The shop was a sauna of heat and humidity. Perspiration rolled from her forehead. After ten minutes, she surrendered and went out to sit by the door where she might catch a breeze.

She found little relief. The still air promised an uncomfortable night.

“Would that we could have a day of rain, Mary Bradbury,” a woman said.

“Goody Dodge,” Mary said. “I shall stand in it until it soaked my clothing.”

“Have you anything for stomach complaints?” Good Wife Dodge asked.

“You know I do. What does the complaint be?”

“My Good Husband has suffered pain for the past day.”

Goody Dodge explained the problem. Mary listened, nodding as the woman spoke.

“It troubles him most grievously.”

“Come in,” Mary said.

She waved the woman through the door into the broiling hot room. Mary searched the shelves and chose a brown, dried root.

“Make tea,” she said. She cut the root in half and handed a piece to the woman. “Cut it thus, in sections, for six. He should take a gill in the morning, thence afternoon, and the last at night. Continue the treatment for two days.”

Goody Dodge looked relieved. “It will offer a cure so quickly?”

“Do not let your husband stray far from the house. It will clean him out.”

“I thank thee. Where learn you all this? You be such a wonder.”

“Most comes from my mother, who taught me from a young age,” Mary said.

Good Wife Dodge lowered her voice. “Be wary. Thomas Walcott again speaks against you.”

Mary glanced toward the door. “He wishes my home and shop. Where thinks he I am to live should I agree?”

“The news from Salem Town emboldens him. Six are now hanged there. Near two hundred more await the gallows.”

“I will take care. He well knows I do not be a witch.”

“He has much influence in Danielsford,” Goody Dodge said. “Many will follow him and what he professes.”

“They know, too, I am a Bible woman.”

“They know Thomas Walcott has money and influence. The people will do his bidding.”

Good Wife Dodge was right. Mary did not argue. If Walcott succeeded, she knew a trial would find her guilty. News of the Salem troubles reached the village, and it worried her. Almost without exception, they found the accused guilty. Danielsford was no different.

She chose not to think about it. What happened would happen. She walked Goody Dodge to the door.

“It does not seem wanting to cool down tonight,” she said.

“Never have I seen it like this,” Goody Dodge said. “It must change.”

“In God’s good time. We are at His mercy.”

“Thank you, Mary. I will start the remedy tonight.”

Goody Dodge left. Mary watched her walk away and returned to her seat beside the door. It was later than her usual time, but she loathed going inside where the heat was worse.

An hour later, she sighed, closed the door to her shop and went around to her home. She made a quick dinner and went to bed, praying the heat would leave the next day.

Just as she dozed, she heard a loud knocking on her door followed by a woman’s voice.

“Mary Bradbury. Please answer. We are desperate.”

Mary rolled from the bed and hurried to the door. She did not recognize the woman in the darkness.

“My son, Benjamin,” the woman said. She rattled off the boy’s ailment.

“It sounds most troubling,” Mary said. “Allow me to dress and we will go to the shop. Tell me again of his sickness.”

While she dressed, the woman repeated the story. Benjamin felt ill after supper. His discomfort increased as the evening wore on until he developed a high fever just before bedtime.

“No one else in the family is sick?” Mary asked.

“Only Benjamin,” Good Wife Smyth said. “My husband is with him. He asked me to come to you.”

“I dislike what I hear,” Mary said. “I must see him.”

“Please hurry,” Goody Smyth said.

Five minutes later, they were on their way to the Smyth homestead at the edge of town. Mary carried several jars of herbs and tonics in a cloth bag. Based on the description, one of her medicines ought to give the boy relief but, if her suspicions were correct, she knew there could be no cure.