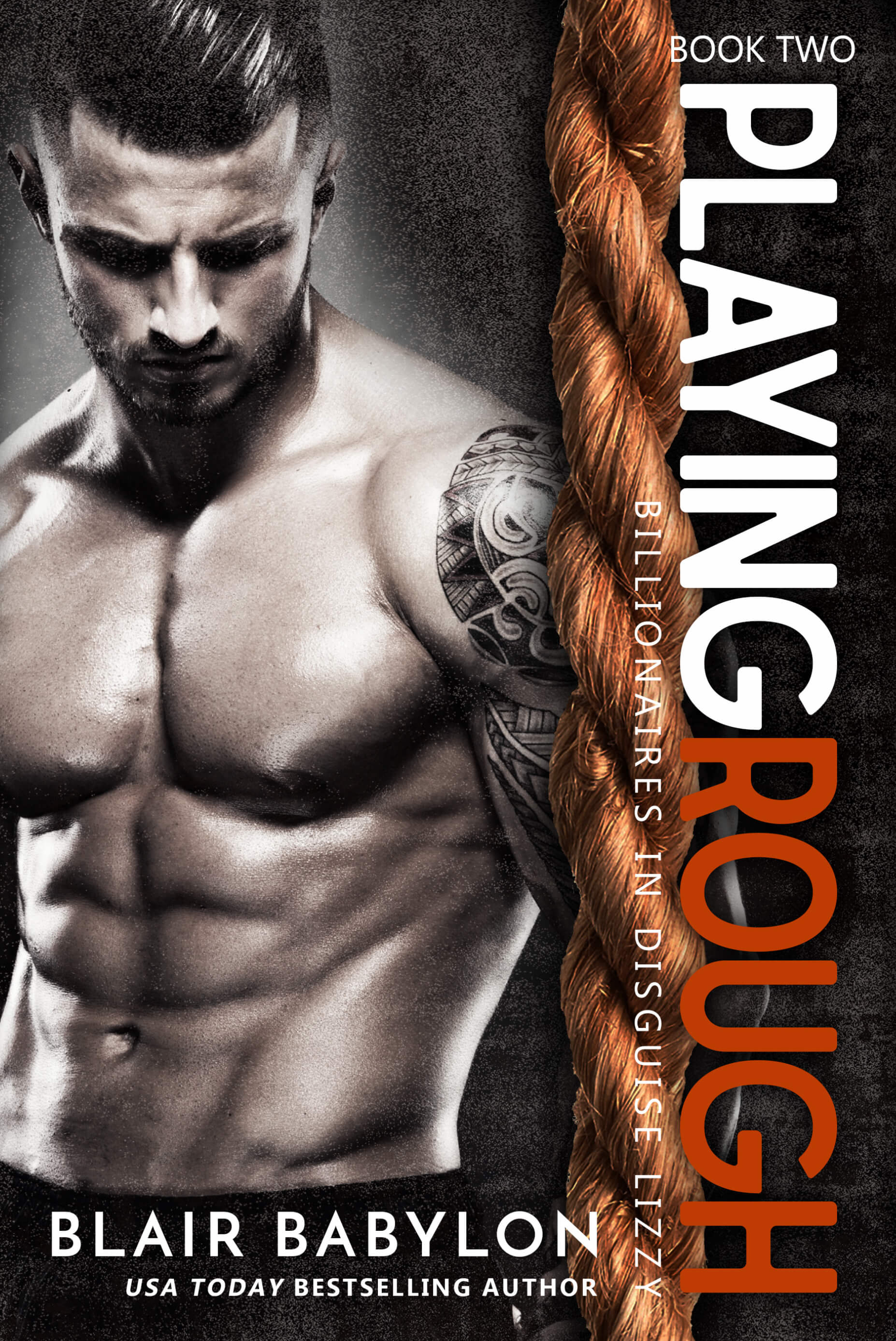

Playing Rough

Synopsis

!! Mature Content 18+ Erotica Novel!! Be careful whom you submit to. Lizzy is trapped. Mannix and Theo have bought The Devilhouse. Her estranged parents want her to quit college to coach Olympic-level gymnastics, the life she escaped. Mannix demands that she give up more control and becomes rougher, more frightening. When Theo offers to help her leave, should she stay with Mannix or go back to the life she thought she had escaped?

Playing Rough Free Chapters

I, Lizzy | Playing Rough

↓

* * *

The jet airplane flies eastward over the ocean, toward Paris, toward The Dom and Rae.

I huddle in the wide first-class seat, turned sideways to sleep, trying not to think about it all. The wide seat makes me look like an abandoned doll.

Beside me, Georgie has reclined her seat into a bed. Her long, brown hair snarls on the airline blanket, and she looks younger than she usually does, maybe nineteen. She keeps waking up and patting my hand. “Sleep,” she says. “Tomorrow might be a long day.”

I promise to try. I lie some other utter bullshit to her about being fine now. My short blond hair feels fuzzy on my head, ruffled by static in the dry, recycled airplane air.

Big airplanes have always scared me. When I’m driving a car, I’m in control of my destiny. Even though the pilots are highly trained, blah, blah, blah, I hate when someone else makes all my decisions for me.

You would think that it would be a relief, to give up all your responsibility and be a child again, even if your own childhood was not idyllic, like everyone else’s must have been. You think you might get a second chance to be a child, to do it right this time, maybe with someone who loves you, and maybe you’ll be stronger when you grow up again.

That’s stupid.

First, even if you think you’re giving it all away, you’re not. Other areas of your life will rear their ugly, Russian heads to drag you down into that special pit of pain that they built, or yet other things will shake their multitudinous heads and demand that you take action when they’re threatened. You can’t ever escape. You can only fight back.

Second, absolute power may corrupt absolutely, but giving up power makes you weak. Weakness is pain when it is in the body.

Last, be careful who you give your power to. They won’t value you after they have it.

Lizzy in Beijing | Playing Rough

↓

* * *

When Lizzy was sixteen years old, her parents sent her home from Beijing on a hospital flight paid for by the US Olympic Committee, rather than allow Chinese surgeons to operate on her.

At least, that’s what they told the world in front of the television cameras during their press conference. The cameras flashed and hummed, recording their every studied gesture, every eyebrow flicker, every cough. The podium dwarfed Lizzy’s mother Svetlana, but her mighty father had ended up leaning on it on his elbows, doubled over.

Lizzy could have stayed. She had begged to stay, even though it would have taken massive doses of painkillers to keep her from passing out. You could get horse tranquillizers from the Chinese doctors. The other girls had gotten all sorts of things from the Chinese gymnasts that, they swore, wouldn’t show up on the IOC drug screens, mostly mild painkillers to allow them to train harder.

If Lizzy had stayed, she could have been part of the team, at least there to support her friends whom she had trained with and competed against for more than a decade. Quince and Jann had lived in her parents’ house and shared Lizzy’s bedroom for three years. They had worked at their fake home-school curriculum around the kitchen table for an hour every night, which was mostly hand-copying responses to fan mail from little girls and middle-aged men.

They were all but sisters, desperately competing for her parents’ attention and a place on the Olympic team. Jann and Quince had given Elizaveta the nickname Lizzy.

But Lizzy’s parents sent her home.

She argued. She pleaded. She couldn’t even get out of the bed to lock her hospital room door.

Nyet, they said. She must be hidden away.

They didn’t want the distraction, they told her.

Really, they didn’t want her sitting on the sidelines, her injuries speaking to the other girls, telling them to be cautious because every vault could be their last. Any misstep might plummet them onto the balance beam and kill them. A dragged toe could break their neck on the floor exercise.

The other girls needed to be fearless, because fear was weakness.

The hospital plane had roared through the sky, stopping in Honolulu for fuel and supplies, and then landed at Newark. The nurses transferred her to an ambulance and sped her to the hospital.

The press had been in New Jersey, too, flashing their cameras, jostling her gurney, all for a glance and a photo of tragic little Elizaveta Pajari, pale and tiny and huddled on the stretcher, her blond ponytail lying limp on the white pillow.

On the television, one commentator, a crusty old contrarian with blue hair and a matching skirt suit, had asked if the risk for such a traumatic, life-threatening injury to a child was worth having the competition, but the Olympics had proceeded and the reporters lionized the competitors and the victors, thus answering her question.

Once the competitions began, the focus was on the medal winners, and wounded bird Elizaveta Pajari faded away.

In the celebrity vacuum left by Elizaveta’s withdrawal, an unknown girl from Venezuela won the individual all-around gold.

The Chinese won the team all-around.

Without Lizzy, her team had lost.

From her hospital bed, even through the opiate haze, when the television cameras had zoomed on their four stoic faces painted with glitter and US flags, Lizzy could see the crushing knowledge that they had lost everything they had trained for, had given up everything for, their whole lives.

Elizaveta’s face faded away from the television screens and the newspapers.

Her name limped away from people’s memories.

Late one night, months after the Olympics were well over, after the plaster and fiber casts had been cut off and the pins had been unscrewed from Lizzy’s flesh and bones, on yet another night when her parents were training young hopefuls at Pajari Gym and did not visit her, Lizzy opened a back door from the hospital to a Newark alley and, at sixteen years old, faded away from the hospital into the New Jersey winter night.

Within a few hours, she learned that she should have waited until it was closer to morning. The streets are more dangerous in the dark, and there was nowhere to escape from the icy wind.