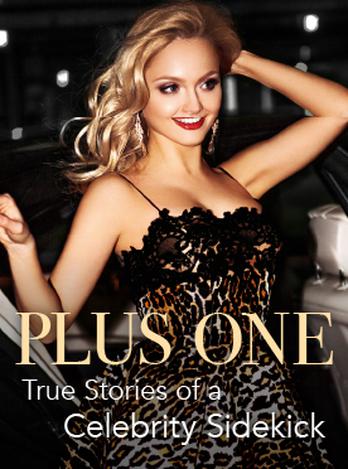

Plus One: True Stories of a Celebrity Sidekick

Synopsis

Everyone thinks they know Madison Dahl. They pour obsessively over glossy magazines and trashy tabloids, reading about Madison's latest movies and parties and secrets, but for all the crumbs of her life that they fight over, none of them know the real stories. But me? I know them all. In Hollywood, they talk about people who have "it" and people who don't. Erin Park's best friend, Madison Dahl, had it. But she definitely didn't have it all.

Plus One: True Stories of a Celebrity Sidekick Free Chapters

Chapter 1 | Plus One: True Stories of a Celebrity Sidekick

↓

“You wouldn’t believe what a geek I was as a kid. A raging geek. I got picked on a lot, too. Terrorized, actually. But hey, success is the best revenge, you know? I mean, where are those kids now? Knocking over 7-11s? Actually, that’s probably giving them too much credit. I doubt any of them would be bright enough to open the cash register.”

—Madison Dahl in Vogue magazine Everyone thinks they know Madison Dahl. All those Star and Us Weekly subscribers think they’ve got the whole dish, even the dirty secrets. They’ve read about which celebrities Madison’s supposedly slept with, her real hair color (dark ash blonde, NOT platinum), the time she got wasted off her ass and danced on the tables at Butter with Lady Gaga. It’s not that none of that is true, because it is, even though her “people” always deny it, soulless liars that they are. It’s just that there’s so much more—true stories no one will ever, ever read about. I know it all, but I’ll never spill, especially not to some scumbag reporter.

See, Madison and I have known each other since we were kids. She would probably die if I told a tabloid she was so shy, she used to eat her lunch in a toilet stall of the girl’s bathroom. And I’m not even sure anyone would believe me if I told them that Madison, perfect, gorgeous, A-list Madison, used to have buck teeth. And I’m talking about serious, point-and-whisper-behind-her-back buck teeth.

They were cute when she was little and got her plenty of TV commercial gigs, but she had to wear monster metal headgear for almost two years of middle school. It’s funny to think about now that we’re adults, but I bet she would agree those were the toughest years of her life. Yes, even after all the hell she’s been through. I think it’s because when you’re a kid, you’re still so soft, so vulnerable. Madison hasn’t been either of those things for a long, long time.

I hope it doesn’t seem like I’m slamming Madison, or that I’m jealous. Sure, I used to be when we were younger—I’ll cop to it. I’d see her getting ready for a premiere, a stylist fluttering around her like a fairy godmother while a make-up artist covered her zits with some high-tech airbrushing gizmo, and I’d wish just once, someone would lavish me with that kind of attention. I used to feel that way, but not anymore. Everyone thinks they want to be famous, but that’s only because they haven’t seen what being a star is like close up. And believe me, for all the glamour and hype, it’s not as great as you’d think.

***

When I met Madison, she still went by her real name: Maryanne Fedderbit. Yes, that’s the name on her birth certificate, which sounds about as Hollywood as an Iowa cornfield. But back when we were in seventh grade, it sort of fit. Maryanne was going through an “awkward stage,” according to her mom, Sheila. Mrs. Fedderbit tried to be cool by letting everyone, even her daughter, call her by her first name. But she was never, ever cool with me. Even then, I thought she was a witch with a capital B, which was a pretty big insult by my geeky seventh-grade standards.

I still remember Maryanne, I mean Madison, walking into class looking like she was being led to her own execution, her eyes darting around the room and her face deathly pale. If you squinted, you could see some of the things that landed her on People magazine’s “50 Most Beautiful” list last year, but it was hard to put the pieces together back then.

Sure, she had the silky blonde hair (stuck in a prissy ponytail) and the enormous green eyes (which were, as I already mentioned, crazily darting around). But that all took a backseat to the stuff that was wrong. And there was a lot that was really, really wrong.

She was wearing a plaid skirt and this horrible blue sweater with a cartoon duck on the front. Seriously. A big yellow duck, like something you’d see on a baby. Oh, and don’t forget the headgear, although Madison would love it if you did. Go to Madison’s house in the Hollywood Hills now, and there are tons of pictures of her from magazine covers and movie posters, but you won’t find a single one of her wearing her headgear or braces. She even tore her face out of all our old class photos, if you can believe it.

Anyway, Mrs. Simpson, our old gargoyle of an earth sciences teacher, made Madison stand in front of the class so she could introduce her. That’s the worst, and I know because I went through it myself two years earlier when my parents moved to Beverly Hills from San Francisco. I still remember looking out into this sea of cold, pitiless eyes and feeling like everyone was furiously hating me. Madison must have felt the same way because her face turned whiter and whiter the longer Mrs. Simpson yapped.

“And Maryanne comes to us from, where is it, sweetheart?” You could tell Mrs. Simpson was either having a good day or feeling sorry for Madison because she called her sweetheart. Usually, she just yelled your full name. “ERIN KIM, where is your homework? Bring it up NOW”—that sort of thing.

“I’m from Oxnard,” Maryanne muttered, putting a hand over her braces as she opened her mouth. She spoke so softly, I almost didn’t hear her, but the kids at the front of the class sure did. From the back of the room, I could see their shoulders shake as they tried to muffle their laughter. “Oxnard? Posh!” I heard Alexandra Waterman sneer.

Of course Alexandra looked down her nose at Oxnard, a little beach town up the coast. She thought anyplace that wasn’t Beverly Hills or, like, Paris was hopelessly un-chic. Alexandra was one of those girls who begged her mommy for a Fendi purse and actually got it and wore Seven jeans before anyone else knew they were trendy. Basically, if the girl could have had a designer label tattooed on her forehead, she would have.

When my parents moved to Beverly Hills, I thought it was going to be fun, like that old TV show “Beverly Hills 90210,” where all the kids hang out at a diner and listen to live bands. Boy was I wrong. Most of the kids at my school were snobby and rude, always bragging about their parents’ new Ferrari or their latest hiking trip to Peru. The others were socially awkward dorks or bullies who held down kids’ heads in the toilet for fun. I kept to myself and stayed quiet, and as a result, I got pretty much left alone. Sure, sometimes kids would make fun of me because I’m Korean, pulling at their eyelids to make them look slanted, but if I ignored them, eventually, they forgot about me.

I could already tell it wouldn’t be that easy for the new girl. There were just too many things to make fun of, like the goofy sweater and the headgear. But mostly, it was the expression on her face. She looked so scared, even I could tell it would be easy to torture her. She’d obviously never fight back. I almost felt sorry for her.

I say almost because when Mrs. Simpson assigned her to sit next to me in the back of the room, I wanted to crawl under my desk and die. The absolute last thing I needed was to be associated with the class punching bag.

I stared at my pencil and prayed this pathetic loser didn’t catch my eye, or worse, smile at me. I didn’t really have close friends at school, just a few other outsiders I could eat lunch with, but I sure didn’t want a friend like her if she was going to be walking anthrax.

And to think I was already embarrassed to be in this chick’s zip code before she puked on my shoes.

I think it was just after lunch that Madison threw up in class, right in the space between our two desks. At first, I thought she was just leaning over to pick something up. But then, I heard a gurgling noise, which would have been embarrassing enough because it was plenty loud. I wasn’t the only person who turned and stared at Madison, and I’m sure that didn’t help.

After that, everything happened lightning fast. She puked so violently that what was left of her lunch splattered all over the floor (and, as you know, my shoes) with this awful liquid splash. And then, I smelled the puke. It was the nastiest odor you can imagine, like some sick experiment involving rotten meat, brussels sprouts, and battery acid. I don’t know what she had to eat at lunch, but it looked like vegetable soup with little bits of corn. Just remembering it now makes me feel queasy, and to this day, I still can’t eat certain kinds of soup.

Then, as everyone started yelling and running across the room with their hands over their faces, Madison lowered her head onto her desk and started to cry. I’m not even sure anyone else heard her, what with everybody freaking out and Mrs. Simpson screaming, “IN YOUR SEATS, NOW! STUDENTS, SETTLE DOWN!” But I did. It was such a sad, broken sound, it made me want to cry a little, too.

Mrs. Simpson finally had the common sense to walk Madison down to the nurse’s office, and we didn’t see the new girl for the rest of the day. But I knew that as bad as her first day of school was, her second day was going to be a lot worse. Already, some of the bullies were coming up with nicknames for Madison.

“Did you get a load of Malibu Barfie?” Alexandra cackled to her friends. “Must have been that vomitous outfit of hers. Made me want to throw up, anyway. And that headgear! She looked like a hockey goalie!” Cassie, a chubby blonde who followed Alexandra everywhere like a dumb puppy, just about fell out of her chair, she was fake laughing so hard, the creep.

But it was Roger Ott, the class thug, who was really psyched about Madison’s big purge fest. “Hey, I think we should call the new girl Feddervomit,” he screeched, pointing at the puddle as the janitor covered it with red sawdust, then mopped it up.

I think everyone in class secretly hated Roger, who was as dense as he was big. Sometimes, I’d see kids roll their eyes at his lamest jokes (and they were all pretty lame), but no one dared cross him. He’d been held back at least two years, and he was huge, even for a kid his age. Roger was taller than Mrs. Simpson and bulky in that football player way, kinda fat but strong, too. You knew just by looking at him, with those squinty eyes and that slash of a mouth that looked crooked razor wire, that he was a bully. And now, he’d set his sights on Madison.

Yeah, it was already pretty clear that Madison’s first year at Westhaven Middle School was gonna suck.

***

“She threw up in the class?” My mother stopped setting the dinner table for a minute, and her eyes went wide. “Next to where you sit?”

“Yes, mom, right next to my chair.” My mom was from South Korea, and even though her English was really pretty good, sometimes I had to repeat things.

“Did someone take her to the doctor?” It was only five o’clock, but I could already smell dinner bubbling away in the kitchen. Steamed rice, of course, and bulgogi, which is this really spicy beef barbeque that is possibly the best thing my mom cooked. She did some American things, like hot dogs and chicken soup, but she mostly liked to cook the kinds of food she ate back in Seoul.

“I guess so. She didn’t come to class today. I’m sure she’ll be back tomorrow.”

“Invite her over,” Mom said in a voice that was definitely not a question. “Make a friend.”

“I have friends,” I muttered. What I really wanted to say was, “Are you completely insane?”, but then my mom would start lecturing me about respecting my elders and how my snotty attitude would never be tolerated where she comes from, blah di blah di blah.

“Make another friend. You have a lot in common.”

“Like what?” I knew I sounded pissed off, but I was. What could I possibly have in common with this stupid girl with the ducky sweater and the chunks of puke stuck in her headgear? I may not have been popular, but I wasn’t a total loser, either.

“You’re new to the school; so is she.” My mom smiled. “She could be a new best friend. You never know until you try.” She always liked any opportunity to use some American catch phrase like “just do it” or “don’t let them see you sweat.” When she first came to the States, my mom learned a lot of English watching bad TV, and it showed.

“Fine, whatever.” I figured it was just easier to go along, then never do it and hope Mom forgot about it. I just couldn’t bear the thought of adding one more thing to the list of stuff my mom and I fought about because we fought about almost everything. She picked on me about how clean my room was, what I wore, and whether or not I spent enough time playing the cello, which I hated.

She just had no clue what it was like to be a kid in America, and she had all these psycho ideas about how I was supposed to behave and dress. The biggest brawl we ever had was when we went shopping for school clothes, and she wouldn’t let me buy jeans because they weren’t “ladylike.” Can you believe that? My dad finally broke down and brought home a pair for me, just plain old Levis from Target, and told my mom that all the guys he worked with at his aerospace company let their girls wear jeans. After that, she finally broke down. But if it wasn’t for my dad, my mom would have been sending me to school wearing crap like Madison’s stupid ducky sweater.

Mom looked at me, hard, like she could see right into my brain. “If you don’t make plans, I will call the school and ask them to give me her mother’s number, and I will make plans.” God, it was like she was psychic or something whenever I wanted to disobey her. I sometimes think she had some sort of super spy microchip installed in my brain so she could read my thoughts. You laugh, but if it existed, my mom would’ve been first in line to buy it.

“Okay! I’ve got homework,” I said, pushing away from the dinner table and grabbing my backpack. I ran to my room, but even locking the door behind me, I couldn’t block out the sick feeling I had in my gut. This stupid new girl was going to completely screw up my life.

***

When I walked into class, Madison was already in her seat. Her outfit was more normal than the previous day’s fashion disaster, just jeans and a t-shirt, but it didn’t make any difference. Everyone was pointing and whispering about her, and it was like that the whole day.

I knew I had to talk to her at some point, but I just couldn’t do it. I tried to sit near her in every class we had together, but whenever I thought about talking to her, Roger would be turning around in his seat and sticking his finger down his throat, making gagging noises. And then at lunch, when I thought I might casually talk to her in the cafeteria line, she disappeared. Poof. Just gone. Years later, she told me she would eat lunch in a bathroom stall every day, her feet up on the seat so no one could see them.

Finally, at 2:25, I realized I had exactly five minutes to get this play date crap over with, and I still hadn’t done it. So I tore a scrap of paper out of my binder, scribbled, “Want to hang out?” on it, and slid it to her.

Madison just looked at it, folded it in half, and looked at Mr. Davis, our English teacher, at the front of the room. She didn’t look at me, didn’t take out her pen, nothing.

I couldn’t believe it. Here was the school’s biggest loser of all time, and she was blowing me off! I was just about to tear out another scrap of paper and write, “My MOM made me ask because she felt SORRY for you, you dumb ass!”, but just then, she turned, looked at me, and nodded. She looked scared, like she was waiting for bad news.

Only then did the truth hit me. She probably thought I was setting her up for a practical joke because who in their right mind would want to hang out with her, especially now?

***

That Saturday, I pushed the buzzer to Madison’s apartment and waited while my mom watched from the car. She was a little pissed that I didn’t invite Madison over to our house, which would have been “proper manners,” but I had convinced her that Madison really wanted me to come over. The truth is I never liked having kids over to my house. Other kids had PlayStations and their own computers and TVs, but my big sister Victoria and I didn’t have anything like that. There was one TV in the living room that my mom always had set to the Korean language station or CNN, and we couldn’t even touch my dad’s computer except to do homework.

When we lived in San Francisco, I invited one of my friends over and thought everything was fine until the next day, when she told everyone we had stinky roots in jars all around the house like witches and that all our furniture looked like salvage from a Chinese restaurant. It was a total lie. Most of our furniture was from IKEA, and she was so dumb, she didn’t even realize that kimchi isn’t a root at all, just this super spicy pickled cabbage you can buy at any grocery store. And it wasn’t all over the house, anyway. My mom had a little refrigerator that was just for kimchi so we could keep it at the right temperature and it didn’t stink up the other stuff in our regular fridge. A lot of Korean families have kimchi refrigerators, so it was no big deal. But that was the last time I invited anyone over, no matter how much my mom complained.

“Hi.” It was Madison’s voice on the intercom. She still sounded kind of nervous, which came as no surprise. All week long, the teasing had been getting worse. One day, I had suggested to the kids I ate lunch with that we invite Madison to sit with us, and they looked at me like I’d lost my friggin’ mind.

“No way,” said Amy, a chubby girl who sometimes helped me with my social studies homework. “Like, Roger only just stopped picking on me when she got here. It’s her turn now.”

I knocked on Madison’s apartment door, and a woman opened it. Her face was almost as red as her hair, and she was dripping with sweat. From her goofy pink leotard and the towel around her neck, I guessed she’d been exercising. “You must be Erin,” she said, waving me inside. “I’m Madison’s mom. You can call me Sheila. Anyway, welcome to Chez Fedderbit!”

Calling the place “chez” anything seemed much too fancy because the apartment was small and dark and smelled musty. People think you have to be rich to live in Beverly Hills, but the truth is a lot of people rent rundown apartments in the city just so they can say they live in the 90210. Looking around, I wondered if Madison wished she still lived in Oxnard. None of the furniture matched, and the orange shag carpeting was so ugly, it was hard to look at.

Madison popped up from the sofa. “Hi,” she said again.

“Hi.”

And the conversation died right there.

Sheila looked at her daughter like she was the most pathetic person on earth. “Madison, why don’t you show your friend around your room so I can get back to my workout tape? I swear, if I didn’t know better, I’d think you were slow.”

I think right about then was when I started hating Sheila.

After Madison showed me her room, which was just as dark and small as the rest of the place, we still didn’t have a lot to talk about.

“Do you like horses?” Madison asked.

“Not really.” I’d ridden one once and hated every minute. My horse kept wandering off the trail to eat stuff, and it smelled awful, like hay and crap. Which makes sense, I guess. Of course, Madison was obsessed with them—even knew the kind she wanted to get someday. A palomino pony.

“Do you collect anything? I collect teddy bears.”

She pointed to a sad little pile of stuffed animals in the corner next to her bed, and I have to say, I thought that was the dumbest thing I’d ever seen. Teddy bears are fine—if you’re six. But we were practically teenagers.

“I have a cat named Bree. And I Rollerblade,” I said, trying hard to resist the urge to call my mom and beg for her to pick me up. “And I play the cello.”

“Oh.” Madison looked disappointed. “Want to play cards? Or Uno?”

This was worse than visiting my great aunt at her nursing home in Long Beach. “Is there anything else to do?” I looked at my watch and couldn’t believe that just fifteen minutes had passed. My mom said she’d pick me up at 4, which was three hours and forty-five minutes from now.

Madison looked at her hands. “Want to see my portfolio?”

“What’s that?” It sounded weird, but at least it was better than Uno.

“I used to be a model,” she said. She reached under the bed, pulling out a thick binder and flopping it onto the covers.

I almost started laughing because I thought for sure she was making this up. If Madison was a model, then I was a world class brain surgeon. But then, she opened the binder.

Madison flipped through the photos, and there were a lot of them. Madison as a little girl in a yellow swimsuit next to a bottle of sunscreen. Madison as a baby gobbling up a spoonful of strained peas. Madison modeling a goofy sweatshirt, Madison naked next to a bottle of baby lotion.

“I did this one for Coppertone, and this was a national ad for Johnson & Johnson. I was in a commercial for them, too. Sometimes, you can still see it on TV.”

“Wow,” I said, flipping back through the pictures. “That’s really cool.” And it really was.

“My mom says I made a lot of money, but we can’t spend most of it until I’m 18,” Madison said. “I’m going to use it to go to college. I want to study drama.”

Madison smiled then, and for just a minute, I could see that beneath the headgear, she was actually kind of pretty.

“You want to be an actress?” I could just imagine what my mom would say if I told her that. I’d be living out of a suitcase under a freeway overpass before I could even finish the sentence. And even then, my mom would make sure I packed my cello.

“I’m already an actress, really. I did a lot of commercials.

“That sounds fun.”

Madison’s eyes lit up. “Someday, I’m going to win an Oscar. I know it. I was born to be an actor. My mom even says the first time she took me to an audition, everyone in the room said I was the most talented kid there. It’s all about being able to draw on your life experience. You have to show people your heart, show that you know what it’s like to hurt.” The light in Madison’s eyes abruptly dimmed. “That’s easy for me.”

I nodded, not really knowing what to say. I wasn’t that passionate about anything. Sure, I’d fantasized about being a famous actress, but I didn’t really think about it beyond being loved by adoring fans and looking gorgeous. Madison, though—she had it all worked out.

“Maybe later, we can watch my reel,” Madison suggested. “If you want to.”

“Sure, why not?” This was kind of fun. Even though I lived in Beverly Hills, I didn’t actually know any real actors. They send their kids to hoity-toity private schools, so it’s not like I took classes with celebrity spawn or anything. Sometimes, you’d see an old star like Cher or Pierce Brosnan at the Ralph’s on Beverly picking up groceries, but that wasn’t very exciting. And it’s weird because most of the time, unless someone’s a paparazzo or a huge fan, no one who lives in L.A. ever bothers a star when they see one. I think it’s because we all know they’re just trying to go about their business like the rest of us, and you’re supposed to pretend you aren’t really seeing them in their sweatpants with no make-up on.

But here was Madison with this big, crazy secret and a trust fund to boot. I guess I must have looked pretty shocked by everything because Madison reached out and slammed her portfolio shut with this sad look on her face. “You think it’s stupid, don’t you?” She said it like it wasn’t a question but a statement of fact.

“It’s not that. You just seem so…shy. Like on the first day of class.”

As soon as the words escaped my lips, I regretted them. Madison crossed her arms over her chest, and her mouth settled into a scowl. “Even big stars get stage fright, you know,” Madison said, her voice sounding more than a little defensive. “And I hadn’t gotten a lot of sleep the night before. Sometimes that makes me feel…queasy.”

“I’m not criticizing you,” I said quickly. “I’m just saying I thought you’d be more out there, being an actress and all.”

“School is different. With a camera and a director, you have a job to do. You have a script. Everything’s all mapped out. Acting is a lot easier than real life.” When she spoke again, she covered her mouth with her hand. She hadn’t done it all day, not until just that moment. “But I’m taking a break from acting,” she muttered.

“She’ll work again. As soon as we straighten out those horse teeth.” Sheila was leaning in the doorway, wiping sweat from her face.

Out of the corner of my eye, I could see Madison’s spine stiffen, as if she’d been hit. Sheila reached over her shoulder and flipped back to one of the baby pictures. “That was a cute one. Never should have let those teeth come in. Should have just capped them right from the get-go and called it a day. You might have gotten a series then. But blame your father. That’s from his side of the family. Maryanne, did you ask your little friend if she was hungry?”

Madison and I both shook our heads.

“Swear to God, you have the manners of a barnyard animal. Well, if your friend gets hungry, you know where the peanut butter and crackers are. But I don’t want you pigging out. Once the pounds go on, they’re hell to get off,” she said, laughing as she squeezed her thigh, which looked pretty skinny to me.

I watched Sheila walk out of the room. “Wow. Your mom was kind of harsh.”

Madison shrugged. “She says she just wants me to get a dose of reality. No one ever tells the truth in this town.”

“You don’t have to be mean to tell the truth.” In what alternate reality is telling someone they have horse teeth constructive criticism?

“She says she’s helping me toughen up. It’s working great, huh?” Madison made a face that told me it really, really wasn’t. “Are you sure you don’t want to play Uno?”

I was, but we played anyway. All I could think about was how suddenly, my own mom didn’t seem so horrible to me anymore. Really, when I compared my life to Madison’s, it didn’t seem bad at all.

***

After that, Madison and I found out we did have a few things in common. Like. we both loved Mexican food and *NSYNC (this was seventh grade, okay? Like you didn’t love them back then). And surprisingly, Madison actually had a pretty good sense of humor. She could do a dead-on impersonation of Roger, right down to his walk, which was like a limping elephant but less graceful.

That Monday at school, it was a lot harder to listen to Roger and the other cretins make fun of Madison. So at lunch, I made my decision. I would eat with her, even if no one wanted to sit with us, and my so-called friends pretended we didn’t exist. Looking back, it doesn’t seem like such a big deal, but back then, it felt like I was walking in front of a speeding Metrolink train with my eyes closed. Like I was crazy and damn near suicidal.

“Um, okay,” she said, her eyes darting in that nervous way of hers. I don’t think she had completely ruled out the possibility of betrayal.

“Monday’s taco day,” I said in my most encouraging voice. “It practically tastes like real food. Kind of.”

Almost the second we set our trays down at a table, one so far in the back of the room, it was practically in the lawn outside the building, it started. I hadn’t even taken a bite of my taco when I looked up to see Roger hovering over us, that nasty slit of a mouth upturned into something resembling a smile.

“Well, if it isn’t Feddervomit! Are you going to be able to keep all that down, or should I eat it for you?” Roger reached onto Madison’s tray and scooped up a handful of fruit salad. Then, holding it next to his face, he pretended to puke, dropping the grapes and cantaloupe onto the floor with a sickening plop. “Ooops, looks like Feddervomit couldn’t hold it!”

Madison said nothing, but I could see tears welling up in her eyes.

“Cut it out, Roger,” I muttered.

“What are you, her bodyguard? She paying you now?” Roger asked in a mocking voice. “I bet you’re cheap, like everything else they make in China.”

Madison’s mouth dropped open, but I wasn’t surprised. Roger was the king of the cheap shot, even if it meant being a racist pig.

I figured it was time to play Madison’s one ace. “You know something? Madison’s an actress. She’s been in commercials.”

It wasn’t only Roger and his buddies who laughed when I said that, and I immediately regretted it.

“What commercials did you do? Pepto-Bismol? Adult diapers?” Roger cackled.

Madison’s face was so red, I thought she might explode. I felt instantly awful. Why hadn’t I known that Roger would find a way to make something cool sound embarrassing?

“What’s going on over here?” It was Mr. Weil, the art teacher. Mondays, he was also the lunch monitor, and I’d never been so glad to see him.

“Can I be excused?” Madison said quickly, jumping up from the bench.

“Me, too,” I said. I wasn’t about to get left alone with Roger, even if that meant I wouldn’t get to eat lunch that day.

Mr. Weil nodded, and we ran out of the cafeteria, the sound of laughter echoing off the walls behind us.

***

In the bathroom, I checked the stalls to make sure we were alone. “I am so sorry. I thought that telling him about your commercials would shut him up.”

“It’s no big deal,” Madison muttered, but I knew that it was. Her work was the one thing she felt proud of, and now, thanks to me, some nimrod was coming up with a whole goodie bag of insults about it.

“God, I hate him!” I said, tearing a paper towel into shreds just to keep my hands busy. “HATE him!”

“Me, too.” Madison sat on the edge of the sink, looking exhausted. “I’m sorry you got pulled into this. He shouldn’t have said that stuff about China. That was horrible.”

“I’m not even Chinese. I’m Korean. Man, I can’t believe he’s so stupid, he can’t get his racist slurs right.”

Madison smiled, but weakly. It was a long moment before she spoke again. “I don’t know what to do, Erin. I really don’t. Everybody hates my guts but you.”

Her voice sounded so hopeless and lost, I stopped tearing up the paper towel. I hardly knew Madison, but I knew enough to think that if this went on, day in and day out, something really bad was going to happen. Something that couldn’t be fixed. No one can be expected to get up each morning and go to school knowing that they are going to get kicked around, ridiculed, and humiliated, and there’s nothing they can do about it.

“Look. We’re going to come up with a plan, okay?” I said. Madison barely nodded, looking at her shoes. “Okay? You have to help me out here. I can’t do this alone.” I made my voice sound as much like my mother’s as I could, the voice she used when I had no say in the matter. Which was the voice she used most of the time.

It seemed to work. Madison looked me in the eye, and for once, she didn’t look away. “Okay. I mean, it can’t get any worse, anyway.”

For some reason, I started thinking about Madison’s portfolio. She always looked happy and confident in her pictures, nothing like the frightened kid standing in front of me. “You’re a good actress, right?”

Madison looked kind of nervous but nodded. “I think so.”

“It’s time for you to act like the person you want to be. Act like someone who isn’t the least bit afraid of Roger Ott.”

Madison thought about it. “I’m not sure I’m that good. That’s, like, Oscar-winning good.”

One of my mom’s stupid catch phrases popped into my head. “You’ll never know until you try, right?”

At last, Madison smiled. “Right.”

We came up with a lot of lousy ideas, crazy ones, but it wasn’t until right before the bell rang that we decided on a plan. We knew it could backfire; we knew it didn’t make a lot of sense. But we were desperate enough to try it.

And the best part? Madison proved to everyone, me included, that she wasn’t just a good actress. She was a great one.

***

Tuesday was meatloaf day, and Madison and I loaded up our trays with so much crappy cafeteria food, we could barely lift them. I got two Jell-O desserts, a slice of cake, extra green beans, and two cartons of milk, plus extra gravy on my meatloaf. Madison got pretty much the same thing but with a chocolate pudding instead of the cake. We looked like pigs, but we didn’t care.

“Well, looks like Feddervomit wants to barf up a lot! Man, everybody stand back—she’s gonna blow chunks big time!” Roger roared as he looked over our trays. It took him even less time to find us this time, since we had picked a table right in the middle of the cafeteria.

Roger picked up Madison’s chocolate pudding and, once again, pretended to barf it up. Even I could tell the joke was getting old; his buddies laughed half-heartedly at best.

I felt Madison squeeze my hand beneath the table. It was go time.

“No, no, NO!” I yelled at Roger with the kind of voice you’d use on a naughty dog. “Don’t you know ANYTHING?” I don’t know how long it took me to notice it, but the cafeteria had gone deadly silent. Everyone was looking at us, frozen in mid-chew. “Binging and purging is VERY Beverly Hills. In fact, your momma does it, right?”

Madison stood up. “Geez, you’d think repeating seventh grade so many times, you’d pick up a few things,” she chirped while Roger stared at her in shock. “Here, let me show you how to throw up. I’m really good at it.”

Madison picked up her green beans and bent at the waist, clutching her stomach and moaning. Slowly, she let the green beans dribble to the floor as she made the most disgusting retching sounds I’d ever heard. Right away, you could tell she’d be a good actress, at least in horror movies.

“What is wrong with you? You’re totally stupid!” Roger said in a squeaky voice, but no one was paying attention to him. For once, Madison and I were the center of attention, and it wasn’t such a bad thing.

“See, Roger, if you knew anything, you’d know it’s a slow, gradual movement,” I said, making some revolting noises of my own as I let my meatloaf plop onto the floor.

Madison and I looked at each other, and that was it. We started giggling, and when we saw the frightened looks on everyone’s faces, we just laughed harder. Cackling like lunatics, we picked up the food on our trays and tossed it onto the floor. Madison even did a little bit of her imitation of Roger, though she was laughing so hard, I’m not sure anyone recognized it.

For the record, I’d like to say I wasn’t the person who threw an apple at Roger’s head. But when we saw it bounce off that thick skull of his, we looked at one another and just knew what we had to do without saying a word. We both reached onto our trays and grabbed up enormous fistfuls of food, green beans and gravy and God knows what else, and pelted Roger with it all, full force.

Of course, in our enthusiasm, we hadn’t factored in an important little detail. Roger was a big guy. Really big. And now he was really mad. And, yelling his head off, he lurched forward, his long gorilla arms reaching for us.

We were running, but I could feel his hand tugging on the back of my shirt, and when I looked to the side, I saw him clawing at Madison’s hair, which slipped through his fingers like silk thread. But he was already tightening his grip on my shirt, twisting it with his hand. And I knew he wasn’t going to let Madison get away so easily, either.

Lucky for us, that was the exact moment when Roger’s sneakers slid into the pudding.

BOOM! Roger went down hard. By this time, the food fight had started in earnest around us. Lunch bags and milk cartons whizzed through the air like grenades, and kids were screaming their heads off, so I never heard the crack. But I wasn’t the only one to hear Roger scream. And I wasn’t the only one to stare, in shock, when he started to cry. I don’t mean the kind of quiet sniffling you see at funerals or weddings, either. I mean, sobbing like a little kid who skinned his knee, snot running down his face, and these wounded animal noises coming out of the back of his throat.

“YOU BROKE MY LEG!” he wailed.

I almost walked over to him, but just then, Mrs. Jetter, the Spanish teacher, grabbed both Madison and I by the arms to drag us to the principal’s office. We never saw the rest of the food fight, or the paramedics who came to take Roger to the hospital. But everyone in the school had it in their heads that the whole mess was our fault, not Roger’s or even that unknown apple thrower’s. Not that we minded.

Sitting outside Principal Zinner’s office, I squeezed Madison’s hand. “That was so cool,” I whispered. “I mean, I feel bad about Roger, but still.”

Madison grinned back. I don’t think I’d ever seen her smile—not like that, anyway. You know the look. It’s the one you’ve seen on the cover of magazines and in movie posters. She seemed genuinely happy, but it was something else. She looked triumphant.

“Yeah, sure. I feel kinda bad about that, too. But otherwise?” she whispered back. “It was the coolest.”

***

I was feeling pretty good until the principal called us in. I’d never been in his office before. After all, I’d always been a goody two-shoes, getting mostly straight A’s and winning awards for my science projects at the county fair. Seeing his big, bald forehead wrinkled up disapprovingly, it suddenly struck me that, as much fun as we’d had, we were in trouble. Big trouble.

“Sit down, girls,” Principal Zinner said, his voice rumbling and deep. Mrs. Jetter stood by his side, looking more worried than angry.

Principal Zinner started talking about things I hadn’t even thought about, like how much the school would have to pay in overtime to the janitorial workers cleaning up our mess, and how upset our parents were going to be about this. Just thinking about what my mom and dad were going to say made me want to throw up for real.

I was busy calculating how many years my parents were going to ground me when Mrs. Jetter interrupted the principal, who seemed to be building up to some big, dramatic finale in which Madison and I were going to be burned at the stake.

“Principal Zinner, I don’t know the whole story, and what the girls did was obviously wrong,” she said quietly. “But I will say they’ve never been a problem in my class. Roger Ott, though—he’s a different story. I know he’s been teasing Madison, and I’m certain he has something to do with this. When he gets back from the hospital, his first stop is to visit you.”

Principal Zinner blinked quietly, like he’d hit his head on something and didn’t know where he was. He looked at us, then Mrs. Jetter. And sighed. Then, he sent us back to class with one week of detention, which is what most kids get for skipping class and other minor stuff. I swore that from then on, I was going to become Mrs. Jetter’s best Spanish-speaker, even better than the Mexican kid in my class whose first word was agua.

We got off easy, but even if we hadn’t, even if we’d been suspended or forced to clean the whole cafeteria by ourselves with a single Q-tip, I think it would have been worth it. Because after that day, our whole lives changed.

Instead of being the classroom puker and the Korean girl, for the rest of the year, we were the girls who broke Roger Ott’s leg and started a food fight in the cafeteria. We weren’t pathetic losers anymore. We were, well, troublemakers. Bad girls.

It didn’t make us any more popular. But no joke, I think people started respecting us. They didn’t talk over me when I spoke in class or bump into Madison in the halls without apologizing. Roger didn’t insult Madison anymore, at least not to her face. And that was absolutely fine with us.

The funny thing was Madison liked being thought of as dangerous a lot more than I did. She started walking straighter, laughing louder. After a month or two, I realized I hadn’t seen her eyes darting around in a long time.

“You were right, you know, about acting like the person I wanted to be,” she said to me one day. “But the cool thing is, once you do, and you see that people believe it, you actually become that. And now, well…” She grinned. “I’m kinda fearless.”

I wish I could have said to her that I was too. I look back on that day in the cafeteria and think it was the one time when I really stood up for myself. Madison walked away from our little adventure completely transformed. All I got out of it was detention.

But sometimes, I wonder if that day, that pivotal triumph over Roger Ott, was the beginning of all Madison’s problems. Maybe if that food fight had never happened, she wouldn’t have been crazy-brave enough to do the things she did later when the paparazzi were watching. Then again, if Roger Ott hadn’t pushed her to go a little nuts, maybe she’d never have had the guts to go as far as she has, and the fans wouldn’t love her as much.

All I know for sure is from then on, that shy, scared girl with the darting eyes disappeared forever. And that could never be a bad thing.

Chapter 2 | Plus One: True Stories of a Celebrity Sidekick

↓

People think I’m going to parties all the time, but I’m not really like that. I’d much rather spend time with my friends watching DVDs at home or bad reality TV. We order pizzas, hang out, catch up, just like anyone else. Parties are fun, sure. But my friends—they’re everything to me.

—Madison Dahl in Teen People magazine I hardly noticed, but by the middle of ninth grade, Madison’s braces had done their dirty work. So one day in November, she walked onto the school grounds transformed, a butterfly sprung from her steely cocoon. No wires, no headgear, no more metal mouth. She was beautiful, and no one could deny it. And from that moment onward, everyone started treating Madison differently.

See, beautiful people, truly beautiful people, have this thing about them that makes people want to be near them. They want to talk about them, analyze them, stare at them like they’re exotic animals in the zoo. You don’t have to be a celebrity, either. That year, our first at Beverly Hills-Glenoaks High School (we just called it Bev Hills), was when I got a taste of what it was like to be in a star’s orbit, even though no one knew she was going to be a celebrity back then. But already people were paying a lot more attention to Madison. Some of it good, some of it bad.

The bad was that even at Bev Hills, Alexandra was still the queen bee of the popular girls. Amazingly, she and her suck-up groupies had become even cattier since middle school. Instead of hissing “retard” and “geek” in the hallways, they moved on to sneering “slut” and “whore” at Madison. Which was stupid, because until Madison lost the headgear, she wasn’t getting a lot of attention from guys.

Personally, I’d rather just tell you about the good part. People started saying hi to us in the halls, which was a huge shock after Westhaven. Sometimes kids would save seats for us, and guys were always offering to do Madison’s homework. And then there was Kelly and Jenna.

I hadn’t really noticed that Kelly and Jenna had been sitting at the same table as Madison and me during lunch. Thanks to all the crap we used to get in middle school, Madison and I had gotten really good at tuning people out, so much so that sometimes people would have to repeat things a couple times before I’d realize I was being spoken to. So I was a little surprised when Jenna slid down the cafeteria bench and tapped her finger on my lunch tray.

“Hey, are you guys trying out for cheerleading?” she asked, tucking a strand of red and black hair behind one ear. Jenna was all-out goth, with black lipstick and black nails and a black leather jacket.

“No, are you?” I sneered in my most sarcastic voice. I naturally assumed she was trying to insult me. Like I looked like the cheerleading type, come on!

“Yeah, actually,” she said, serious as a heart attack.

“We want to bring down a misogynistic, frivolous institution from the inside,” Kelly added. If you didn’t know Kelly and Jenna, it was hard to see what they had in common, because Kelly wasn’t goth at all. She was strictly a jeans and t-shirts girl, straight auburn hair, no make-up. But never trust a plain brown wrapper. If anything, Kelly was more of a rebel than Jenna.

“And there’s always the bonus of making Alexandra miserable,” Jenna said. I knew enough about Jenna and Kelly to know Alexandra was about as mean to them as she was to Madison. She called them the “bull dykes” and said Jenna looked like the lead singer of My Chemical Romance.

“I like the way you think,” Madison said, smiling.

“Probably because we do think,” Kelly said. “Unlike everyone else at this school.”

Madison and I looked at each other. These two girls were going to be fun. Trouble maybe, but fun.

After that, we all started eating lunch together, and then hanging out on weekends. When Kelly and Jenna made the cheerleading team (which predictably made Alexandra, who only got onto the team after another girl dropped out, absolutely furious), we even went to see them cheer, knowing they’d sneak in some slightly obscene hand gestures or make faces at Alexandra behind her back during half time.

Madison and I finally had our own clique, our own gang. Even though sometimes I missed it just being Madison and me, mostly I was thrilled to know I had these two cool girls in my corner. So when my life got turned upside down, I was so grateful Jenna tapped on my lunch tray all those months earlier. I couldn’t know it then, but the day was coming when I’d need all the support I could get.

***

“I can’t believe Greg Fromer has a crush on me. GREG FROMER!” Madison was combing her hair in front of her vanity mirror, angrily pulling at a stubborn knot. For the last year we’d been fixing up her bedroom, and I no longer minded hanging out there, even with Sheila around. The teddy bear collection was hidden in a box in the closet (and if you’re wondering, yes, she still has it), and now Madison had bright pink walls and band posters instead. We’d even bought old furniture at Goodwill and painted it black and white. I’m sure she’s thrown all of it away since then, but we loved it at the time.

“Why is that so unbelievable?” asked Kelly, sitting cross-legged on the floor. “He’s a walking hormone.”

“But this is the guy who followed me around school making metal mouth jokes for a full year at Westhaven,” Madison said. “Is he freakin’ dumb?”

“Well, yes,” said Kelly. “You’re just figuring that out?”

“I wish I needed braces,” Jenna sighed from where she was flipping through Madison’s CD collection. “They would go perfectly with the eyebrow piercing I want.”

“You’re insane,” Madison said.

“I’m not the one with a suck ass Maroon 5 album,” Jenna shot back.

“I’m totally going out with him. Just so I can dump him,” Madison said.

“Make him buy you a nice dinner. And flowers,” Kelly suggested.

“Then stomp on his heart like a grape. Love that,” Jenna added.

“Don’t be so hard on Greg, Madison. He’s sickeningly in love with you,” I said, squeezing a pink and purple pillow to my chest.

“I know,” Madison grinned. “That’s the best part.”

I hated talking to Madison about boys. Even after Westhaven, I had pretty much forgiven most of the jerks at school and could honestly say some of the guys were pretty nice. One boy in my chem class, Brandon, was even insanely cute. But did I ever get asked out? No way.

But since she lost the braces, Madison was knee deep in testosterone. The thing was, she had become a heartless, malicious tease. Cruel wasn’t even an overstatement. Alexandra had it all wrong when she called Madison a slut. When it came to guys, she was just a bitch.

She’d wink at a guy in the hallway, then make fun of him mercilessly once he was out of earshot. She’d go out with guys for a few weeks, wait for them to fall madly in love with her, then dump them cold. She’d make them do stupid things to prove their love for her, like wear a bow tie and suspenders to class, then laugh at them when they tried to kiss her. As far as she was concerned, all the guys at school were worse than dirt. And she treated them that way.

“These lame ass high school boys bore me,” she’d sigh after she found yet another love letter stuffed in her locker, barely reading it before she crunched it up and tossed it in the trash.

“Then why go out with them?” It killed me that Madison was running through guys like Kleenex when I’d kill to just have someone to make out with, but I never told her that.

“Something to do. Every girl needs a hobby,” Madison said. “And besides, I don’t want a real boyfriend. Not when I’m focusing on my career.”

Or, rather, Sheila was focusing on Madison’s career. Madison hadn’t been exaggerating when she said her mom wanted her auditioning as of yesterday once her braces came off. Just a few days after Madison got her new smile Sheila stuck her in the car and drove her to the modeling agency she had worked for when she was a kid. It figured. Sheila always seemed a lot more interested in Madison when she thought she could make some money off of her.

Since we’d already covered the topic of breaking Greg Fromer’s heart, I figured I might as well ask about her one true love. At least I wouldn’t have to hear about any other hearts she longed to obliterate. “Any new jobs?”

“Maybe, but I’m only doing a little modeling,” Madison said, carefully putting mascara on her top lashes. She’d already done one photo shoot, but she’d picked up a ton of hints from the make-up artist there, like using blush to make her face look thinner and how a little white eye pencil makes your eyes “pop.” “I told my agent I’d only work for her if she got me a theatrical agent, too, for acting. Sheila about had a fit, you know.”

“Why? Doesn’t she want you to be an actress?” Kelly asked, absentmindedly painting a toenail black using a felt-tipped pen.

“Oh, definitely. There’s a lot more money in it than modeling, so that makes Sheila happy. But she doesn’t want me turning down any jobs, whether they’re modeling or acting. She totally doesn’t get that I need the right kind of exposure. National commercials, not just regional crap.”

“Can’t she see you’re a star, dammit?” Jenna howled, banging her fist on the floor.

It was weird to hear Madison talking about “the industry” (as she liked to call it). It seemed so foreign and scary to me, but she loved everything about it. Talking about “the trades” (really boring daily newspapers about the movie business) and “weekend grosses” (what a movie made over the weekend) was a lot more interesting to her than talking about the boys at school, even the ones I thought were cute.

I hopped off the bed. “I should call my mom,” I said. “She wants me home for dinner.”

“I wish you could stay.” Madison made a frowny face. Sometimes she still did things that made her seem like a little kid, like sulking when she was mad or making faces. It was funny, because Madison had hit puberty (and hard) in the last year. She hadn’t grown much taller, but she was filling out a 34C bra. Oh, like you thought the boys just liked her for her nice new teeth? Please. Sheila actually made Madison wrap an ace bandage around her chest when she went to the modeling agency so she’d look younger. But with a little make-up she definitely looked her age, whereas I looked like I was still twelve. I didn’t even need to wear a bra, but I did anyway.

“I wish I could stay, too,” I sighed. Even eating Sheila’s crummy casseroles was better than going home these days. The situation between my mom and me had escalated from mild mutual irritation to full-scale warfare. After pushing me so hard to become friends with Madison, she started griping about her plenty after the food fight. Like we were the bad guys in that scenario.

The funny thing is, Madison really liked my mom. The few times I had her over, she followed my mom around the house, complimenting her taste in wallpaper and her cooking. At first I thought she was just being a suck-up, but even when we were alone, she went on and on about her. For whatever reason, Madison was my mom’s biggest fan.

“I know you two don’t get along, but I so wish Sheila was even a little like your mom,” Madison said as we sat in my TV-less, computer-less room. “Your mom is a really positive person, you know. It’s pretty impressive to think she came all this way to a foreign country where she didn’t even know the language to make a life for herself.” I kept waiting for the sarcasm, the punchline, but it never came.

Of course, I never had the heart to tell Madison the things Mom said about her when she wasn’t there. I mean, I was glad one of us loved my mom so much.

It didn’t help when my mom met Sheila, either. The first time Sheila came to our house to pick up Madison, she was wearing a pair of hip hugger jeans and a tank top that showed her belly button. My mom hated her instantly. It didn’t matter that I did, too. Mom kept saying corny things like “Apple doesn’t fall far from tree, Erin.” She actually thought Madison was going to end up becoming just like her mom, a “woman of loose morals, like the ‘Pretty Woman.’” And nothing I said would convince her otherwise.

When my mom came to pick me up from Madison’s, it was the same old crap. “What did you do all day with that Madison?” my mother said with a scowl. “I don’t like that girl, Erin. Not good for you.”

Sometimes, hearing Madison talk about how she was going to tear some poor guy apart for sport, I kind of agreed with her. As much as I loved Madison, she had started doing stuff that really bugged me. But at least I still liked her more than I liked my mom. So I just didn’t say anything, and we drove most of the way home in silence. As usual.

***

“Erin, time for dinner,” my sister Victoria yelled through my bedroom door. It was a Wednesday night, so that meant Mom was probably making something gross, like Chicken Cacciatore.

“In a minute!” I yelled back. Madison had just called, and she was squealing so loud I thought I’d never get my hearing back. Whatever had happened, it was big.

Victoria stuck her head into my room. “Mom’s gonna freak. She’s in a crappy mood, I’m warning you.” Victoria sometimes bugged me, but ever since she got into UCLA she’d been a lot nicer. I’m sure it had something to do with knowing she’d be moving out of the house soon, which must have been a huge relief even if it meant living in some crappy dorm. But I think even she could tell things were so bad between me and Mom that somebody had to run interference. Dad sure wasn’t up to the task.

I nodded at Victoria but didn’t hang up. “Make it quick, Madison, really quick,” I muttered into the receiver.

“I got an audition! For a movie!”

“Are you serious? What is it, who do you play, oh my GOD!”

Now there was a banging on the door. Mom.

“Dinner, NOW!”

“Madison, I’ll call you back, gotta go,” I whispered, then stuffed the phone under my pillow and picked up a book.

Just then the door opened. “What are you doing in here?” Mom looked pissed. She worked as a real estate agent, and it had been a while since she made a sale, so I knew it wasn’t entirely about me.

“Reading.” I said.

“No, you weren’t,” Mom snapped back, taking the book out of my hands and turning it right side up. Oops. “You were talking on the phone.”

I didn’t say anything. I figured lying more would just get me into bigger trouble.

“When I say it’s dinnertime, you come to dining room. No more phone for rest of week.”

“Mom!” I was truly going to explode if I couldn’t call Madison back. I mean, it was one thing when we were just sitting on the phone talking about Justin Timberlake (oh, I’ll admit it, big crush there), but this was serious.

“Keep sassing me, no phone for month.”

You’ve got to understand, I was so angry I just couldn’t hold it in. My words leapt out of my mouth, as if I had Tourette syndrome and no control over myself. “God, I hate you,” I hissed.

My mother just stared at me for a long, awful moment. I think she was waiting for me to apologize. And I wanted to, I really did. But I was still so mad at her. She was always on me to study more, practice the cello more, be more like my sister, and I was tired. Tired of not being what she wanted me to be, and especially tired of her hating my best friend, the one person in the world who actually understood me.

Basically, I was tired of being a big, stinking disappointment.

“Dinner,” Mom said simply, and walked out of the room.

***

After dinner, during which no one talked and we all ate as fast as we could without choking to death, I tried to make a quick escape. “May I be excused?” I asked.

“No,” my mother said. So I sat and watched as Victoria and my dad drifted away to the living room, and then as my mom cleared the table, dish by dish. Finally, she sat down at the table across from me. She crossed her hands in front of her and stared at them for a long time. My mom was the kind of person who was always doing something, cleaning, cooking, making phone calls, so to see her so still and silent was strange. And I knew it was a bad, bad sign.

“You know the phone is a privilege and not a right, yes? We have talked about this?”

Actually, I thought a phone pretty much was a right. I mean, I was the only kid I knew he didn’t have a cell phone, for God’s sake. Giving me a land line seemed like the least my parents could do. “It was an important call,” I said, crossing my arms over my chest.

“What was so important? Someone in hospital? Terrorist attack Los Angeles? What?” Mom’s voice got higher and louder, but I could see she was trying to control it. I knew she must be really mad, so mad she was afraid that if she let loose there would be no way to reign in her anger again.

I just shrugged. I couldn’t help thinking she was overreacting. Fine, I hadn’t rushed down to dinner willy-nilly. So what?

“Victoria never did things like this when she was your age,” Mom said, and her voice sounded sad. Disappointed. “She was always very responsible.”

“Well, I’m not Victoria,” I said, and now it was my turn to hold back some anger. “Sorry I’m such a big letdown for you.”

My mother’s head spun around. “You are not a big letdown to me. You let down yourself.”

“But I don’t let myself down, Mom.” Why couldn’t she understand this? “I’m a good kid, I get good grades. I want to hang out with my friends. I don’t want to be a professional cello player, you know? I want to have a life like everybody else!”

My mom sighed, and she looked older all of a sudden. Tired. “I know you do,” she said softly. “I just think you have potential to be much better. I want you to be all that you can be. Like the Army.”

Well, I didn’t know what the hell to say to that. Part of me was kind of happy. I didn’t know my mom even thought I had potential. But part of me still felt rotten, like the person I wanted to be would never, ever make her happy.

It was a long moment before I said anything. “Aren’t you going to ground me or something? I want to get started on my homework.”

Mom shook her head. “I want us to not be angry at each other, gohng-joo,” she said.

“Okay.” I felt bad that she called me princess. It’s what she used to call me when I was little, when we still got along. This wasn’t what I was expecting at all, but I was hoping it meant I wasn’t going to be stuck in my room for a month.

“Maybe we make a deal. You can spend time with your friends on the weekends. Sleepovers, that stuff. During the week, school. No phone calls. No visits. All school. And cello lessons.”

I didn’t like the sound of no phone calls, but I figured I could agree to it in the short term. “Okay.”

My mother reached out and stroked my hair. “You know Dad and I want the best for you. American dream, all that.”

“Yeah, I know.” I got up from my chair. My mom just stared at me, and I felt like I should say something. Something nice. “Thanks,” was all I could muster.

My mom nodded and got up from the table. She hesitated there, as if there was something else she wanted to say before she headed back into the kitchen to do the dishes. For a second I thought about following her, of helping her load the dishwasher or something, but I didn’t. I wish I had. Maybe she’d have told me what it was she wanted to say.

But the moment passed, and we retreated to our own separate worlds, me doing homework in my room, her washing dishes in the kitchen.

And whatever my mom was holding back, I’ll never know.

***

The next day at school, Madison got Jenna, Kelly, and me filled in on all the details about her audition. She had a shot at playing Tom Hanks’s daughter in a spy movie. It wasn’t a big part because she’d get killed in the first half hour, but it was still pretty enormous to think that she might make her movie debut opposite Tom freakin’ Hanks. There was something funny about thinking that Madison, who used to be the class punching bag, could be a major movie star in a year or two. And I’d be able to say that I was her best friend.

“Hey, do you think you’ll meet Tom Hanks at the audition?” Jenna asked.

“Oh, if you do, you should totally pull down his pants or something. He acts so nice all the time—it would be funny to see him lose his shit.”

“I don’t think he’ll be there,” Madison said. “And I wouldn’t pull down his pants, anyway.”

“You’re no fun!” Jenna said, punching Madison in the arm. “Hey, when you’re a big movie star do you think you’ll be able to get us into Hollywood parties?”

Madison rolled her eyes. “You guys are so lame,” she sighed, but I could tell she liked the idea of sneaking the gang of us into some fancy club and drinking mojitos with Jake Gyllenhaal or something. I liked that idea, too.

Later, Madison pulled me aside. “I go in today at 4 p.m. Apparently, they’ve looked at a ton of girls, and nobody’s been right for it. I guess that’s why they’re willing to talk to a newbie like me,” Madison explained. “I really need you to come along. Sheila’s just going to make me neurotic.”

“There’s no way my mom will let me.” I had already filled Madison in on the big fight the night before. When I had told her what I’d said, Madison’s eyes went wide.

“I’ve never even said that to Sheila.” Madison’s voice was so quiet and serious, it just made me feel more awful about the whole thing.

But now she was tugging on my arm, her voice whiney and high. “You have to go! Sheila will pick me apart, and I’ll go in there and bomb, and it will be all her fault!”

It sounded like Madison was being a baby, but I knew what she said was dead on. Sheila would criticize every little thing about her before she ever got in the door, and by the time she finally met the director or casting agent or whoever, she’d be so beaten down she’d barely be able to read the script. Madison needed a buffer. But did it have to be me?

“Take Jenna. Or Kelly.”

Madison sighed. “Come on. You know as well as I do that they’ll do something crazy. Like find Tom Hanks and pull down his pants.”

I laughed. She was right. But that didn’t solve the little problem of what to tell my mom. I felt like she and I had finally, amazingly come to some sort of truce, so for me to blow it now just seemed stupid. “Let me think about it. Maybe I can figure something out.”

Madison let go of my arm and stared at me. “What does that mean, figure something out?”

“It means I have to come up with a really great lie.” I was already trying to decide if I had the guts to break my own arm or give myself a concussion.

Madison started shaking her head. “No way. You’ve got to ask her. Ask her nice.”

As much as Madison liked my mom, she still didn’t really get her. I knew from our whole sit-down chat that my mom already felt like she’d softened up too much. Just my asking permission to go would be a huge disappointment to her, solid proof I really hadn’t heard a word she said. I was better off with the concussion. “Do you want me to go with you or not?” I asked Madison, knowing I sounded annoyed.

Madison didn’t hesitate. “Absolutely.”

***

Now that I’ve been on so many of the lots around town—Paramount, Warner Brothers, Sony, yada yada yada—it’s funny to look back at that first time and remember how impressed I was. But I have to admit, even now, Disney is a pretty cool place to visit. And I’m not talking about the theme park. Anybody can go to Disneyland. You have to have connections to get onto the Disney lot.

Sheila exited off the 134 Freeway, and I saw the gates almost immediately. The words The Walt Disney Company were printed in graceful lettering on a low stucco wall, and an iron gate surrounded the parking lot. But it wasn’t just any iron gate. At the top of each post were artfully sculpted Mickey Mouse ears. So cute!

We drove up to the gate, and Sheila smiled at the security guard in his little kiosk. He smiled back. Maybe this really was the happiest place on earth.

“We’re here for the ‘Spy on You’ casting call?” Sheila said in this super fake, saccharine-sweet voice.

“Just give him my name,” Madison said in an exasperated voice. Lately, she’d been mouthing off to Sheila a lot more than she ever used to, and Sheila was putting up with it. I guess the prospect of Madison becoming a rich movie star made it easier for her to put up with her kid’s crap.

Sheila ended up not only having to give the guy Madison’s name, but her name, her driver’s license, and a contact person to boot. We even had to pop the trunk of the car for the guard to make sure we weren’t driving a bomb into the place. It was harder getting onto the lot than clearing airport security at LAX.

But once we were inside, I forgot all about the intense security check. The lot was adorable, with perfect green lawns and little street signs for Dopey Drive and Mickey Avenue. The coolest thing was that one building had these enormous, and I mean enormous, like twenty feet high, stone gargoyles holding up the roof that were carved to look like Snow White’s seven dwarves. It wasn’t like going to Disneyland or anything, but it was plenty more fun than most places you could work at.

We walked into the Animation Building, which seemed like a weird name for it because I didn’t see anyone animating anything, just lots of offices with secretaries and desks. We finally found the one office we were looking for and stepped inside.

“We’re here for the auditions,” Sheila said to the receptionist in that buggy plastic voice of hers, telling her Madison’s name and then complimenting the lady on her ugly pink blouse. The receptionist just nodded, then said, “If you’ll have a seat, we’re running a bit behind,” and pointed to the waiting area. I’m guessing she completely saw through Sheila, the ultimate pushy stage mom.

And there in the waiting area, sitting in a handful of chairs with their middle-aged moms, were five other girls who could have been Madison’s clones. They all had long, blonde hair. Blue eyes, perfect skin, ditto. They were all just as pretty as Madison.

And each one of them gave her a cool, appraising once over, then looked away.

It sent a shiver through me, the way you feel when you see the psycho killer in a movie zero in on his next victim. Everyone there was competing for the same thing, but no one was speaking to anyone else, just staring ahead or examining their fingernails. I still can’t quite explain why it creeped me out so bad, but it was just a feeling I got. I think I knew that even though these girls were politely sitting next to each other, they were all quietly wishing the others would drop dead.

Madison just sat down in a chair and leaned back. “Sit up straight,” Sheila whispered.

Madison gave me her “I’m so gonna kill her” look, then nudged her mom. “Scoot over so Erin can sit next to me.”

Sheila stared daggers at her, but she did it.

So there I was, in a deathly quiet room full of angry beautiful girls, their moms, and Sheila. I was trying really hard to remember why I agreed to do this, and why it was worth getting my mom all pissed off, when Madison squeezed my hand.

“I owe you so, so much for this,” she whispered, and that’s when I remembered.

***

When they called Madison’s name, Sheila stood up, too, even though none of the other moms had gone in with their daughters. Madison gave her a dirty look, but it didn’t stop good ol’ Sheila. The controlling bitch was determined to go in.

But when Sheila got to the door, the casting assistant stepped in front of her, blocking the door. “I’m sorry, but we’d really prefer to see Madison on her own,” she said sweetly.

Sheila’s face flushed bright red. “That is not acceptable. I need to be with my daughter.”

Madison looked like she wanted to die right there. “MOM!” she hissed. “I’m fine!”

The casting assistant just smiled as if this weren’t totally horrifying. “She’ll just be a few minutes, so if you don’t mind having a seat—”

“I do mind,” Sheila snapped. “Why do you have to see her alone, anyway? Is there nudity in this film?”

The casting assistant stopped smiling. “Mrs. Dahl, please take a seat.” The way she said it, even Sheila understood that if she didn’t, a security guard was probably going to drag her, me and Madison back to our car and pistol whip us.

Sheila went back over to her seat, but she couldn’t shut up. “I think it’s criminal to separate a mother from her child. Criminal,” she muttered.

The casting assistant rolled her eyes, but thank God she let Madison go into the audition.

It seemed like Madison was in there forever, and sometimes I could hear laughter through the walls. That hadn’t happened with any of the other girls who’d already auditioned, and none of them stayed inside as long as Madison had. I had to think that was a good sign.

But most of the time I was sitting there, I was thinking about my mom and how angry she was going to be. I should have already been home for a few hours by then, and I knew she was worried. I thought about asking Sheila if I could borrow her cell phone, but I didn’t. I still had to come up with an excuse, a really good one.

By the time Madison walked out of the room, I was so absorbed by plotting how I could break a bone or voluntarily throw up blood, I jumped a little.

“Want to meet someone?” she said, smiling.

I shrugged, until I saw Tom Hanks standing in the doorway. Yeah, I know. Tom Hanks.

I don’t think I even understood what he was saying to me for a minute, because I couldn’t get over the fact that Tom Hanks was talking to me and shaking my hand. “I guess you’re the quiet one. Your friend here,” and he gestured towards Madison, “she talks enough for the two of you, I think.”

Madison punched Tom Hanks in the arm, grinning like he was just some regular guy and not a big stinking movie star. “Oh, come on, I don’t talk that much!”

Tom Hanks laughed and shook hands with Sheila, who had the same awed look on her face that I probably did. “It’s so nice to meet you Mr. Hanks, I’m a really big fan,” she stuttered, blushing. It struck me that he must get really tired of hearing that every time he meets someone. Now that Madison’s who she is, I know it doesn’t even register after you’ve been a star for a while, like when people say “bless you” after you sneeze.

But Sheila didn’t stop with simple gushing. Oh, no. She had to go and stick her foot in her mouth. “So, Mr. Hanks, I’ve been wondering why you haven’t done a ‘Bosom Buddies’ reunion. Because, I’ve been thinking, I have a great idea for it if you’ve got a minute. And I’d be happy to produce the project for you. You’d have a much bigger role than that other guy, the blond one.”

Sheila was so clueless about Hollywood she didn’t know she’d broken a cardinal rule: you don’t pitch people you don’t know, especially stars. Why? Because if they ever make a movie anything like your lame-o half-baked idea, you won’t be their “biggest fan” anymore. You’ll try to make a quick buck by suing them. Sad, but you know it’s true.

And yet Tom Hanks just patted Sheila on the arm. “Maybe some other time,” he said, in a much nicer tone than I would have used. Then he looked at his watch. I bet he was wondering how quickly he could get away from Sheila without coming across as a jerk. “Boy, we were in there for a long time,” he said.

He turned to a woman with glasses, probably the casting director, and smiled. “You think we should get a TV in here, Rebecca? So people don’t lose their minds waiting? Maybe a little Dr. Phil would make everyone more relaxed. Or one of those aquarium videos. What do you think, Erin?”

I couldn’t believe Tom Hanks was asking me a question, like he actually cared what I had to say. “I think that would be great,” I mumbled. “You’d want to keep the volume was down low, so people who didn’t want to watch weren’t distracted.”

“You heard the woman,” Tom Hanks said, looking at his pink-shirted receptionist. She smiled at him. “And hey, you could watch your soaps, Jennie. Everybody wins!”

I was just grasping that Tom Hanks had made a decision, even a little decision like this one, with my input, when he shook our hands again. “Nice meeting you,” he before disappearing back through the door with Rebecca the casting director a step behind him.

I couldn’t think of anything to say I was so freaked out on the way back to the car, but Sheila couldn’t shut up. “Whatever you did, you must have done it right, honey,” she said, stroking Madison’s hair. “I could tell he thought of you like his own daughter.”

Madison jerked her head away from Sheila and rolled her eyes. I couldn’t get over how calm she seemed, as if this sort of thing happened to her every day. “I don’t have the part yet. Don’t get carried away.”

Sheila ignored her and kept talking. “We should celebrate. We could get ice cream, the full fat stuff at Baskin Robbins. How does that sound?”

Madison looked at me and shook her head. “We need to get Erin home, Sheila. Like, pronto.”

And here’s the reason why I will never, ever stop hating Sheila. “No, we’re getting ice cream,” she said, driving down Buena Vista towards a Baskin Robbins.

“SHEILA,” Madison yelled, her face turning red. “We have to get Erin home!”

“I really do need to get home,” I said, suddenly feeling super lactose-intolerant.

“It’ll only take a minute,” she said, putting the car into park and walking inside the store. “What do you kids want?

“Nothing!” Madison said, but Sheila ignored her.

Madison and I just sat there, staring at Sheila through the glass doors. All I could think about was my mom. I pictured her sitting at the dining room table, staring at her hands. Losing all faith in me, forever.

After what seemed like an hour Sheila came back and handed us both cups of mint chocolate chip ice cream, which I don’t even like. Then Sheila sat in the front seat and daintily nibbled at hers, as if she had all the time in the world.

“Go ahead, eat!” she said, smiling.

“If we eat, can we leave?” Madison asked, glaring at Sheila.

“Of course we can leave. I just don’t want ice cream melting all over the car seats.”

Madison literally took her cup of ice cream, tilted it up, and let the whole mushy mess slide into her mouth. “Let’s go,” she said, wiping soupy dribbles of ice cream off the sides of her mouth.

I did the same, and Sheila looked at us with total disgust. “You’re supposed to savor a treat,” she said in a prissy tone. “I can tell you’re both going to be as big as houses by the time you’re twenty eating like that.”

But finally Sheila put the car into drive, and we headed for home. And so far my only excuse for being late was an ice cream headache.

***

By the time I flew through the door of my house, I’d come up with a stupid story I was desperately hoping my mom would buy. It was something about being nauseous, so nauseous I couldn’t get on the bus, and then somehow getting a ride from Sheila. The particulars don’t really matter, because I never had to tell the story to anyone.

When I walked inside, Victoria was in the kitchen nuking a frozen dinner, and dad was in the office paying bills. They didn’t seem particularly concerned about my showing up three hours late. That was always Mom’s problem, I guess.

“Where’s Mom?” I asked Victoria.

“I don’t know,” she said. “I’m guessing she’s running late or something. She hasn’t called.”

Boy was I relieved. Somehow I had been lucky enough to dodge this bullet, and I swore I would never disappoint Mom again. I went right to my room and started doing homework, even though I was still feeling a little gross from the ice cream. I even wrote a list of things I was going to do to impress my mom. No TV, not even “American Idol.” I’d play cello at old folks’ homes. All sorts of crazy stuff.

I was so caught up in feeling grateful that I didn’t have the sense to feel worried. But I don’t think any of us really felt worried. Not until we got the phone call from the police.

***

My dad went to identify Mom at the morgue, and Victoria and I stayed at home. We cried some, like when we called our extended family with the bad news, but mostly we just stared at each other, totally in shock. It didn’t feel real at all. I kept thinking that she had to be alive, because I’d just seen her that morning. I know it sounds stupid, but at one point I picked up the DVD remote control, thinking if I could rewind my life, just by a few hours, I could fix everything. It seemed so simple, and yet not simple at all.

After we’d called all the aunts and cousins and even Mom’s family in Korea, which Victoria had to do since she spoke the language a lot better than I did, I called Madison.